The First Party

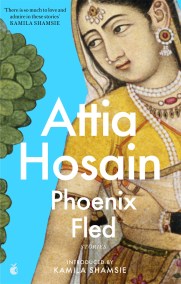

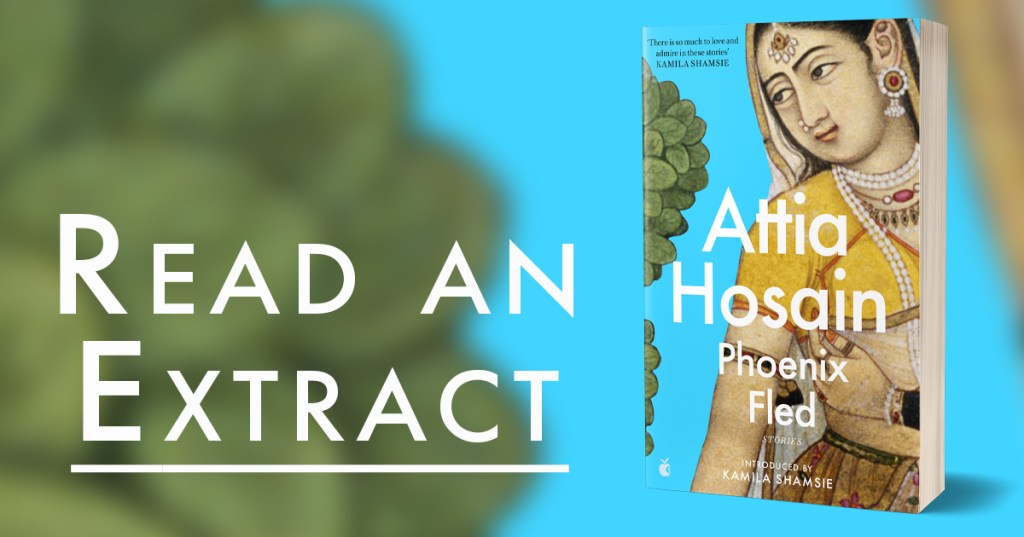

Telling of the lives of servants and children, of conflict between the old traditions and new ways, and exploring the human repercussions of the Muslim/Hindu divide, these twelve stories present a moving and vivid picture of life in India in the mid-twentieth century. To each episode Attia Hosain brings a superb imaginative understanding and a sense of the poignancy of the smallest of human dramas.

After the dimness of the verandah, the bewildering brightness of the room made her stumble against the unseen doorstep. Her nervousness edged towards panic, and the darkness seemed a forsaken friend, but her husband was already steadying her into the room.

‘My wife,’ he said in English, and the alien sounds softened the awareness of this new relationship.

The smiling, tall woman came towards them with outstretched hands and she put her own limply into the other’s firm grasp.

‘How d’you do?’ said the woman.

‘How d’you do?’ said the fat man beside her.

‘I am very well, thank you,’ she said in the low voice of an uncertain child repeating a lesson. Her shy glance avoided their eyes.

They turned to her husband, and in the warm current of their friendly ease she stood coldly self- conscious.

‘I hope we are not too early,’ her husband said.

‘Of course not; the others are late. Do sit down.’

She sat on the edge of the big chair, her shoulders drooping, nervously pulling her sari over her head as the weight of its heavy gold embroidery pulled it back.

‘What will you drink?’ the fat man asked her.

‘Nothing, thank you.’

‘Cigarette?’

‘No, thank you.’

Her husband and the tall woman were talking about her, she felt sure. Pinpoints of discomfort pricked her and she smiled to hide them.

The woman held a wineglass in one hand and a cigarette in the other. She wondered how it felt to hold a cigarette with such self- confidence; to flick the ash with such assurance. The woman had long nails, pointed and scarlet. She looked at her own – unpainted, cut carefully short – wondering how anyone could eat, work, wash with those claws dipped in blood. She drew her sari over her hands, covering her rings and bracelets, noticing the other’s bare wrists, like a

widow’s.

‘Shy little thing, isn’t she, but charming,’ said the woman as if soothing a frightened child.

‘She’ll get over it soon. Give me time,’ her husband laughed. She heard him and blushed, wishing to be left unobserved and grateful for the diversion when other guests came in.

She did not know whether she was meant to stand up when they were being introduced, and shifted uneasily in the chair, half rising; but her husband came and stood by her, and by the pressure of his hand on her shoulder she knew she must remain sitting.

She was glad when polite formality ended and they forgot her for their drinks, their cigarettes, their talk and laughter. She shrank into her chair, lonely in her strangeness yet dreading approach. She felt curious eyes on her and her discomfort multiplied them. When anyone came and sat by her she smiled in cold defence, uncertainty seeking refuge in silence, and her brief answers crippled conversation. She found the bilingual patchwork distracting, and its pattern, familiar to others, with allusions and references unrelated to her own experiences, was distressingly obscure. Overheard light chatter appealing to her woman’s mind brought no relief of understanding. Their different stresses made even talk of dress and appearance sound unfamiliar. She could not understand the importance of relating clothes to time and place and not just occasion; nor their preoccupation with limbs and bodies, which should be covered, and not face and features alone. They made problems about things she took for granted.

Her bright rich clothes and heavy jewellery oppressed her when she saw the simplicity of their clothes. She wished she had not dressed so, even if it was the custom, because no one seemed to care for customs, or even know them, and looked at her as if she were an object on display. Her discomfort changed to uneasy defiance, and she stared at the strange creatures around her. But her swift eyes slipped away in timid shyness if they met another’s.

Her husband came at intervals that grew longer with a few gay words, or a friend to whom he proudly presented ‘My wife’. She noticed the never- empty glass in his hand, and the smell of his breath, and from shock and distress she turned to disgust and anger. It was wicked, it was sinful to drink, and she could not forgive him.

She could not make herself smile any more but no one noticed and their unconcern soured her anger. She did not want to be disturbed and was tired of the persistent ‘Will you have a drink?’, ‘What will you drink?’, ‘Sure you won’t drink?’ It seemed they objected to her not drinking, and she was confused by this reversal of values. She asked for a glass of orange juice and used it as protection, putting it to her lips when anyone came near.

They were eating now, helping themselves from the table by the wall. She did not want to leave her chair, and wondered if it was wrong and they would notice she was not eating. In her confusion she saw a girl coming towards her, carrying a small tray. She sat up stiffly and took the proffered plate with a smile.

‘Do help yourself,’ the girl said and bent forward. Her light sari slipped from her shoulder and the tight red silk blouse outlined each high breast. She pulled her own sari closer round her, blushing. The girl, unaware, said, ‘Try this sandwich, and the olives are good.’

She had never seen an olive before but did not want to admit it, and when she put it in her mouth she wanted to spit it out. When no one was looking, she slipped it under her chair, then felt sure someone had seen her and would find it.

The room closed in on her with its noise and smoke. There was now the added harsh clamour of music from the radiogram. She watched, fascinated, the movement of the machine as it changed records; but she hated the shrieking and moaning and discordant noises it hurled at her. A girl walked up to it and started singing, swaying her hips. The bare flesh of her body showed through the thin net of her drapery below the high line of her short tight bodice.

She felt angry again. The disgusting, shameless hussies, bold and free with men, their clothes adorning nakedness not hiding it, with their painted false mouths, that short hair that looked like the mad woman’s whose hair was cropped to stop her pulling it out.

She fed her resentment with every possible fault her mind could seize on, and she tried to deny her lonely unhappiness with contempt and moral passion. These women who were her own kind, yet not so, were wicked, contemptible, grotesque mimics of the foreign ones among them for whom she felt no hatred because from them she expected nothing better.

She wanted to break those records, the noise from which they called music.

A few couples began to dance when they had rolled aside the carpet. She felt a sick horror at the way the men held the women, at the closeness of their bodies, their vulgar suggestive movements. That surely was the extreme limit of what was possible in the presence of others. Her mother had nearly died in childbirth and not moaned lest the men outside hear her voice, and she, her child, had to see this exhibition of . . . her outraged modesty put a leash on her thoughts.

This was an assault on the basic precept by which her convictions were shaped, her life was controlled. Not against touch alone, but sound and sight, had barriers been raised against man’s desire.

A man came and asked her to dance and she shrank back in horror, shaking her head. Her husband saw her and called out as he danced, ‘Come on, don’t be shy; you’ll soon learn.’

She felt a flame of anger as she looked at him, and kept on shaking her head until the man left her, surprised by the violence of her refusal. She saw him dancing with another girl and knew they must be talking about her, because they looked towards her and smiled.

She was trembling with the violent complexity of her feelings, of anger, hatred, jealousy and bewilderment, when her husband walked up to her and pulled her affectionately by the hand.

‘Get up. I’ll teach you myself.’

She gripped her chair as she struggled, and the violence of her voice through clenched teeth, ‘Leave me alone,’ made him drop her hand with shocked surprise as the laughter left his face. She noticed his quick embarrassed glance round the room, then the hard anger of his eyes as he left her without a word. He laughed more gaily when he joined the others, to drown that moment’s silence, but it enclosed her in dreary emptiness.

She had been so sure of herself in her contempt and her anger, confident of the righteousness of her beliefs, deep- based on generation- old foundations. When she had seen them being attacked, in her mind they remained indestructible, and her anger had been a sign of faith; but now she saw her husband was one of the destroyers; and yet she knew that above all others was the belief that her life must be one with his. In confusion and despair she was surrounded by ruins.

She longed for the sanctuary of the walled home from which marriage had promised an adventurous escape. Each restricting rule became a guiding stone marking a safe path through unknown dangers.

The tall woman came and sat beside her and with affection put her hand on her head.

‘Tired, child?’ The compassion of her voice and eyes was unbearable.

She got up and ran to the verandah, put her head against a pillar and wet it with her tears.

BY ONE OF THE MOST INFLUENTIAL INDIAN WRITERS OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

'There is so much to love and admire in these stories - their understanding of heartbreak, their attention to affection and love across many divides' KAMILA SHAMSIE

'Hosain's greatest strength lies in her ability to draw a rich, full portrait of her society' ANITA DESAI

'Listen to me, child. You will be a woman soon and must behave well and with modesty. The Kazi will ask you three times whether you will marry Kalloo Mian. Now don't you be shameless, like these modern girls, and shout gleefully "Yes". Be modest and cry softly and say "Hoon".'

A marriage is arranged between a little servant girl and a middle-aged cook with an opium habit; an idealistic political worker faces disillusionment; a man returns from years studying in England to a wife he scarcely knows; a conventional bride has her first encounter with her husband's 'emancipated' friends.

Telling of the lives of servants and children, of conflict between the old traditions and new ways, and exploring the human repercussions of the Muslim/Hindu divide, these twelve stories present a moving and vivid picture of life in India in the mid-twentieth century. To each episode, Attia Hosain brings a superb imaginative understanding and a sense of the poignancy of the smallest of human dramas.

Attia Hosain published only two books, but her writing has influenced generations of writers. Discover Sunlight on a Broken Column, Hosain's acclaimed only novel - a coming-of-age story set against the turbulent background of Partition, also published in Virago Modern Classics.