Read The Gift Giving, a holiday short story from Joan Aiken

“Stories are mysterious things; they have a life of their own”- Joan Aiken

In a writing career spanning six decades, Joan Aiken wrote stories of wolves, naughty pet ravens, pirates, necklaces made of raindrops, and much more. This Christmas, we publish a collection of her favourite stories, including The Gift Giving, which you can read exclusively below.

The Gift Giving

The weeks leading up to Christmas were always full of excitement, and tremendous anxiety too, as the family waited in suspense for the Uncles, who had set off in the spring of the year, to return from their summer’s travelling and trading: Uncle Emer, Uncle Acraud, Uncle Gonfil, and Uncle Mark. They always started off together, down the steep mountainside, but then, at the bottom, they took different routes along the deep narrow valley, Uncle Mark and Uncle Acraud riding eastward, towards the great plains, while Uncle Emer and Uncle Gonfil turned west, towards the towns and rivers and the western sea.

Then, before they were clear of the mountains, they would separate once more, Uncle Acraud turning south, Uncle Emer taking his course northward, so that, the children occasionally thought, their family was scattered over the whole world, netted out like a spider’s web.

Spring, summer would go by, in the usual occupations, digging and sowing the steep hillside garden beds, fishing, hunting for hares, picking wild strawberries, making hay. Then, towards St Drimma’s Day, when the winds began to blow and the snow crept down, lower and lower, from the high peaks, Grandmother would begin to grow restless.

Silent and calm all summer long she sat in her rocking chair on the wide wooden porch, wrapped in a patchwork quilt, with her blind eyes turned eastward towards the lands where Mark, her dearest and first- born, had gone. But when the winds of Michaelmas began to blow, and the wolves grew bolder, and the children dragged in sacks of logs day after day, and the cattle were brought down to the stable under the house, then Grandmother grew agitated indeed.

When Sammle, the eldest granddaughter, brought her hot milk, she would grip the girl’s slender brown wrist and demand: ‘Tell me, child, how many days now to St Froida’s Day?’ (which was the first of December).

‘Eighteen, Grandmother,’ Sammle would answer, stooping to kiss the wrinkled cheek.

‘So many, still? So many till we may hope to see them?’

‘Don’t worry, Granny, the Uncles are certain to return safely. Perhaps they will be early this year. Perhaps we may see them before the Feast of St Melin’ (which was December the fourteenth).

And then, sure enough, sometime during the middle weeks of December, their great carts would come jingling and trampling along the winding valleys. Young Mark (son of Uncle Emer), from his watchpoint up a tall pine over a high cliff, would catch the flash of a baggage- mule’s brass brow- medal, or the sun glancing on the barrel of a carbine, and would come joyfully dashing back to report.

‘Granny! Granny! The Uncles are almost here!’

Then the whole household, the whole village, would be filled with as much agitation and turmoil as that of a kingdom of ants when the spade breaks open their hummock; wives would build the fires higher, and fetch out the best linen, wine, dried meat, pickled eggs; set dough to rising, mix cakes of honey and oats, bring up stone jars of preserved strawberries from the cellars; and the children, with the servants and half the village, would go racing down the perilous zigzag track to meet the cavalcade at the bottom.

The track was far too steep for the heavy carts, which would be dismissed, and the carters paid off to go about their business; then with laughter and shouting, amid a million questions from the children, the loads would be divided and carried up the mountainside on muleback, or on human shoulders. Sometimes the Uncles came home at night, through falling snow, by the smoky light of torches; but the children and the household always knew of their arrival beforehand, and were always there to meet them.

‘Did you bring Granny’s Chinese shawl, Uncle Mark? Uncle Emer, have you the enamelled box for her snuff that Aunt Grippa begged you to get? Uncle Acraud, did you find the glass candlesticks? Uncle Gonfil, did you bring the books?’

‘Yes, yes, keep calm, don’t deafen us! Poor tired travellers that we are, leave us in peace to climb this devilish hill! Everything is there, set your minds at rest – the shawl, the box, the books – besides a few other odds and ends, pins and needles and fruit and a bottle or two of wine, and a few trifles for the village. Now, just give us a few minutes to get our breath, will you, kindly—’ as the children danced round them, helping each other with the smaller bundles, never ceasing to pour out questions: ‘Did you see the Grand Cham? The Akond of Swat? The Fon of Bikom? The Seljuk of Rum? Did you go to Cathay? To Muskovy? To Dalai? Did you travel by ship, by camel, by llama, by elephant?’

And, at the top of the hill, Grandmother would be waiting for them, out on her roofed porch, no matter how wild the weather or how late the hour, seated in majesty with her furs and patchwork quilt around her, while the Aunts ran to and fro with hot stones to place under her feet. And the Uncles always embraced her first, very fondly and respectfully, before turning to hug their wives and sisters- in- law.

Then the goods they had brought would be distributed through the village – the scissors, tools, medicines, plants, bales of cloth, ingots of metal, cordials, firearms, and musical instruments; then there would be a great feast.

Not until Christmas morning did Grandmother and the children receive the special gifts which had been brought for them by the Uncles; and this giving always took the same ceremonial form.

Uncle Mark stood behind Grandmother’s chair, playing on a small pipe that he had acquired somewhere during his travels; it was made from hard black polished wood, with silver stops, and it had a mouthpiece made of amber. Uncle Mark invariably played the same tune on it at these times, very softly. It was a tune which he had heard for the first time, he said, when he was much younger, once when he had narrowly escaped falling into a crevasse on the hillside, and a voice had spoken to him, as it seemed, out of the mountain itself, bidding him watch where he set his feet and have a care, for the family depended on him. It was a gentle, thoughtful tune, which reminded Sandri, the middle granddaughter, of springtime sounds, warm wind, water from melted snow dripping off the gabled roofs, birds trying out their mating calls.

While Uncle Mark played on his pipe, Uncle Emer would hand each gift to Grandmother. And she – here was the strange thing – she, who was stone blind all the year long, could not see her own hand in front of her face – she would take the object in her fingers and instantly identify it.

‘A mother- of- pearl comb, with silver studs, for Tassy . . . it comes from Babylon; a silk shawl, blue and rose, from Hind, for Argilla; a wooden game, with ivory pegs, for young Emer, from Damascus; a gold brooch, from Hangku, for Grippa; a book of rhymes, from Paris, for Sammle, bound in a scarlet leather cover.’

Grandmother, who lived all the year round in darkness, could, by stroking each gift with her old, blotched, clawlike fingers, frail as quills, discover not only what the thing was and where it came from, but also the colour of it, and that in the most precise and particular manner, correct to a shade.

‘It is a jacket of stitched and pleated cotton, printed over with leaves and flowers; it comes from the island of Haranati, in the eastern ocean; the colours are leaf brown and gold and a dark, dark blue, darker than mountain gentians—’ for Grandmother had not always been blind; when she was a young girl she had been able to see as well as anybody else.

‘And this is for you, Mother, from your son Mark,’ Uncle Emer would say, handing her a tissue- wrapped bundle, and she would exclaim,

‘Ah, how beautiful! A coat of tribute silk, of the very palest green, so that the colour shows only in the folds, like shadows on snow; the buttons and the buttontoggles are of worked silk, lavender- grey, like pearl, and the stiff collar is embroidered with white roses.’

‘Put it on, Mother!’ her sons and daughters- in- law would urge her, and the children, dancing around her chair, clutching their own treasures, would chorus, ‘Yes, put it on, put it on! Ah, you look like a queen, Granny, in that beautiful coat! The highest queen in the world! The queen of the mountain!’

Those months after Christmas were Grandmother’s happiest time. Secure, thankful, with her sons safe at home, she would sit in a warm fireside corner of the big wooden family room. The wind might shriek, the snow gather higher and higher out of doors, but that did not concern her, for her family, and all the village, were well supplied with flour, oil, firewood, meat, herbs, and roots; the children had their books and toys; they learned lessons with the old priest, or made looms and spinning wheels, carved stools and chairs and chests, with the tools their uncles had brought them. The Uncles rested, and told tales of their travels; Uncle Mark played his pipe for hours together, Uncle Acraud drew pictures in charcoal of the places he had seen, and Granny, laying her hand on the paper covered with lines, would expound while Uncle Mark played:

‘A huge range of mountains, like wrinkled brown linen across the horizon; a wide plain of sand, silvery blond in colour, with patches of pale, pale blue; I think it is not water but air the colour of water; here are strange lines across the sand where men once ploughed it, long, long ago; and a great patch of crystal green, with what seems like a road crossing it; now here is a smaller region of plum- pink, bordered by an area of rusty red; I think these are the colours of the earth in these territories; it is very high up, dry from height, and the soil glittering with little particles of metal.’

‘You have described it better than I could myself!’ Uncle Acraud would exclaim, while the children, breathless with wonder and curiosity, sat cross- legged around her chair.

And she would answer, ‘Yes, but I cannot see it at all, Acraud, unless your eyes have seen it first, and I cannot see it without Mark’s music to help me.’

‘How does Grandmother do it?’ the children would demand of their mothers.

And Argilla, or Grippa, or Tassy, would answer, ‘Nobody knows. It is Grandmother’s gift. She alone can do it.’

The people of the village might come in, whenever they chose, and on many evenings thirty or forty would be there, silently listening, and when Grandmother retired to bed, which she did early, for the seeing made her weary, the audience would turn to one another with deep sighs, and murmur, ‘The world is indeed a wide place.’

But with the first signs of spring the Uncles would become restless again, and begin looking over their equipment, discussing maps and routes, mending saddlebags and boots, gazing up at the high peaks for signs that the snow was in retreat.

Then Granny would grow very silent. She never asked them to stay longer, she never disputed their going, but her face seemed to shrivel, she grew smaller, wizened and huddled inside her quilted patchwork.

And on St Petrag’s Day, when they set off, when the farewells were said and they clattered off down the mountain, through the melting snow and the trees with pink luminous buds, Grandmother would fall into a silence that lasted, sometimes, for as much as five or six weeks; all day she would sit with her face turned to the east, wordless, motionless, and would drink her milk and go to her bedroom at night still silent and dejected; it took the warm sun and sweet wild hyacinths of May to raise her spirits.

Then, by degrees, she would grow animated, and begin to say, ‘Only six months, now, till they come back.’

But young Mark observed to his cousin Sammle, ‘It takes longer, every year, for Grandmother to grow accustomed.’

And Sammle said, shivering, though it was warm May weather, ‘Perhaps one year, when they come back, she will not be here. She is becoming so tiny and thin; you can see right through her hands, as if they were leaves.’ And Sammle held up her own thin brown young hand against the sunlight, to see the blood glow under the translucent skin.

‘I don’t know how they would bear it,’ said Mark thoughtfully, ‘if when they came back we had to tell them that she had died.’

But that was not what happened.

One December the Uncles arrived much later than usual. They did not climb the mountain until St Mishan’s Day, and when they reached the house it was in silence. There was none of the usual joyful commotion.

Grandmother knew instantly that there was something wrong.

‘Where is my son Mark?’ she demanded. ‘Why do I not hear him among you?’

And Uncle Acraud had to tell her: ‘Mother, he is dead. Your son Mark will not come home, ever again.’

‘How do you know? How can you be sure? You were not there when he died?’

‘I waited and waited at our meeting place, and a messenger came to tell me. His caravan had been attacked by wild tribesmen, riding north from the Lark mountains. Mark was killed, and all his people. Only this one man escaped and came to bring me the story.’

‘But how can you be sure? How do you know he told the truth?’

‘He brought Mark’s ring.’

Emer put it into her hand. As she turned it about in her thin fingers, a long moan went through her.

‘Yes, he is dead. My son Mark is dead.’

‘The man gave me this little box,’ Acraud said, ‘which Mark was bringing for you.’

Emer put it into her hand, opening the box for her. Inside lay an ivory fan. On it, when it was spread out, you could see a bird, with eyes made of sapphire, flying across a valley, but Grandmother held it listlessly, as if her hands were numb.

‘What is it?’ she said. ‘I do not know what it is. Help me to bed, Argilla. I do not know what it is. I do not wish to know. My son Mark is dead.’

Her grief infected the whole village. It was as if the keystone of an arch had been knocked out; there was nothing to hold the people together.

That year spring came early, and the three remaining Uncles, melancholy and restless, were glad to leave on their travels. Grandmother hardly noticed their going.

Sammle said to Mark: ‘You are clever with your hands. Could you not make a pipe – like the one my father had?’

‘I?’ he said. ‘Make a pipe? Like Uncle Mark’s pipe? Why? What would be the point of doing so?’

‘Perhaps you might learn to play on it. As he did.’

‘I? Play on a pipe?’

‘I think you could,’ she said. ‘I have heard you whistle tunes of your own.’

‘But where would I find the right kind of wood?’

‘There is a chest, in which Uncle Gonfil once brought books and music from Leiden. I think it is the same kind of wood. I think you could make a pipe from it.’

‘But how can I remember the shape?’

‘I will make a drawing,’ Sammle said, and she drew with a stick of charcoal on the whitewashed wall of the cowshed. As soon as Mark looked at her drawing he began to contradict.

‘No! I remember now. It was not like that. The stops came here – and the mouthpiece was like this.’

Now the other children flocked around to help and advise.

‘The stops were farther apart,’ said Creusie. ‘And there were more of them and they were bigger.’

‘The pipe was longer than that,’ said Sandri. ‘I have held it. It was as long as my arm.’

‘How will you ever make the stops?’ said young Emer.

‘You can have my silver bracelets that Father gave me,’ said Sammle.

‘I’ll ask Finn the smith to help me,’ said Mark.

Once he had got the notion of making a pipe into his head, he was eager to begin. But it took him several weeks of difficult carving; the black wood of the chest proved hard as iron. And when the pipe was made, and the stops fitted, it would not play; try as he would, not a note could he fetch out of it.

Mark was dogged, though, once he had set himself to a task; he took another piece of the black chest, and began again. Only Sammle stayed to help him now; the other children had lost hope, or interest, and gone back to their summer occupations.

The second pipe was much better than the first. By September, Mark was able to play a few notes on it; by October he was playing simple tunes, made up out of his head.

‘But,’ he said, ‘if I am to play so that Grandmother can see with her fingers – if I am to do that – I must remember your father’s special tune. Can you remember it, Sammle?’

She thought and thought.

‘Sometimes,’ she said, ‘it seems as if it is just beyond the edge of my hearing – as if somebody were playing it, far, far away, in the woods. Oh, if only I could stretch my hearing a little farther!’

‘Oh, Sammle! Try!’

For days and days she sat silent, or wandered in the woods, frowning, knotting her forehead, willing her ears to hear the tune again; and the women of the household said, ‘That girl is not doing her fair share of the tasks.’

They scolded her, and set her to spin, weave, milk the goats, throw grain to the hens. But all the while she continued silent, listening, listening, to a sound she could not hear. At night, in her dreams, she sometimes thought she could hear the tune, and she would wake with tears on her cheeks, wordlessly calling her father to come back and play his music to her, so that she could remember it.

In September the autumn winds blew cold and fierce; by October snow was piled around the walls and up to the windowsills. On St Felin’s Day the three Uncles returned, but sadly and silently, without the former festivities; although, as usual, they brought many bales and boxes of gifts and merchandise. The children went down as usual, to help carry the bundles up the mountain. The joy had gone out of this tradition though; they toiled silently up the track with their loads.

It was a wild, windy evening, the sun set in fire, the wind moaned among the fir trees, and gusts of sleet every now and then dashed in their faces.

‘Take care, children!’ called Uncle Emer, as they skirted along the side of a deep gully, and his words were caught by an echo and flung back and forth between the rocky walls: ‘Take care – care – care – care – care – . . . ’

‘Oh!’ cried Sammle, stopping precipitately and clutching the bag that she was carrying. ‘I have it! I can remember it! Now I know how it went!’

And, as they stumbled on up the snowy hillside, she hummed the melody to her cousin Mark, who was just ahead of her.

‘Yes, that is it, yes!’ he said. ‘Or, no, wait a minute, that is not quite right – but it is close, it is very nearly the way it went. Only the notes were a little faster, and there were more of them – they went up, not down – before the ending tied them in a knot—’

‘No, no, they went down at the end, I am almost sure . . . ’

Arguing, interrupting each other, disputing, agreeing, they dropped their bundles in the family room and ran away to the cowhouse, where Mark kept his pipe hidden.

For three days they discussed and argued and tried a hundred different versions; they were so occupied that they hardly took the trouble to eat. But at last, by Christmas morning, they had reached agreement.

‘I think it is right,’ said Sammle. ‘And if it is not, I do not believe there is anything more that we can do about it.’

‘Perhaps it will not work in any case,’ said Mark sadly. He was tired out with arguing and practising.

Sammle was equally tired, but she said, ‘Oh, it must work. Oh, let it work! Please let it work! For otherwise I don’t think I can bear the sadness. Go now, Mark, quietly and quickly, go and stand behind Granny’s chair.’

The family had gathered, according to Christmas habit, around Grandmother’s rocking chair, but the faces of the Uncles were glum and reluctant, their wives dejected and hopeless. Only the children showed eagerness, as the cloth- wrapped bundles were brought and laid at Grandmother’s feet.

She herself looked wholly dispirited and cast down. When Uncle Emer handed her a slender, soft package, she received it apathetically, almost with dislike, as if she would prefer not to be bothered by this tiresome gift ceremony.

Then Mark, who had slipped through the crowd without being noticed, began to play on his pipe just behind Grandmother’s chair.

The Uncles looked angry and scandalized; Aunt Tassy cried out in horror: ‘Oh, Mark, wicked boy, how dare you?’ but Grandmother lifted her head, more alertly than she had done for months past, and began to listen.

Mark played on. His mouth was quivering so badly that it was hard to grip the amber mouthpiece, but he played with all the breath that was in him. Meanwhile Sammle, kneeling by her grandmother, held, with her own warm young hands, the old, brittle ones against the fabric of the gift. And, as she did so, she began to feel what Grandmother felt.

Grandmother said softly and distinctly: ‘It is a muslin shawl, embroidered in gold thread, from Lebanon. It is coloured a soft brick- red, with pale roses of sunset- pink, and thorns of soft silver- green. It is for Sammle . . . ’

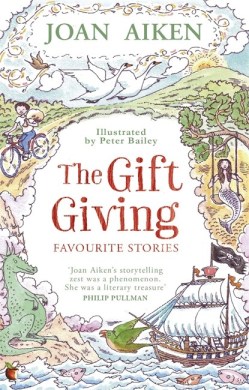

The Gift Giving, a collection of Joan Aiken’s favorite stories, with cover illustrations by Peter Bailey is out now as a Virago Modern Classic for children.