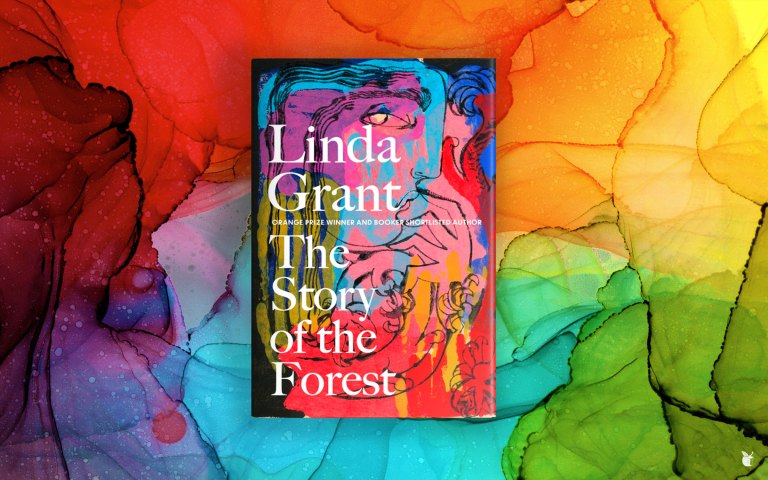

Read an extract from A Stranger City by Linda Grant

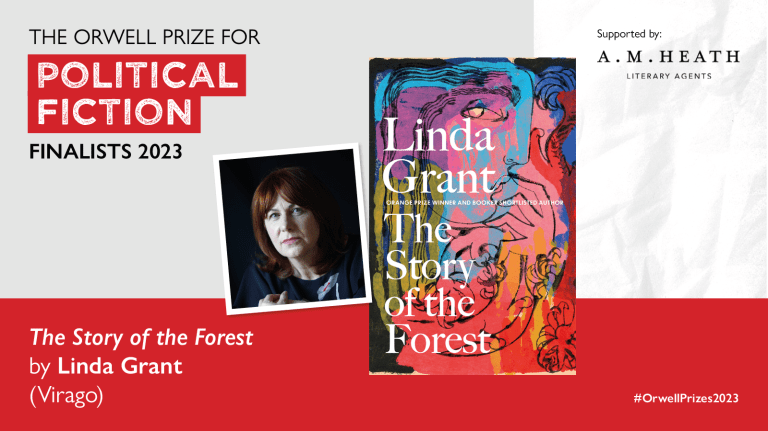

A Stranger City by Linda Grant

When a dead body is found in the Thames, caught in the chains of HMS Belfast, it begins a search for a missing woman and confirms a sense that in London a person can become invisible once outside their community – and that assumes they even have a community. A policeman, a documentary film-maker and an Irish nurse named Chrissie all respond to the death of the unknown woman in their own ways. London is a place of random meetings, shifting relationships – and some, like Chrissie intersect with many. The film-maker and the policeman meanwhile have safe homes with wives – or do they? An immigrant family speaks their own language only privately; they have managed to integrate – or have they? The wonderful Linda Grant weaves a tale around ideas of home; how London can be a place of exile or expulsion, how home can be a physical place or an idea. How all our lives intersect and how coincidence or the randomness of birth place can decide how we live and with whom.

Part One

February 2016

Manor Park, East London

Stranger

She was buried at 9.30 in the morning and as soon as the earth was filled in by the mechanical digger, fog obscured the spot. Sleet was forecast for early afternoon. The four pallbearers, the clergyman and the undertaker watched her go under, standing by the grave in black leather gloves and smart black overcoats. The film crew stood apart; they shot the figures of the six men as bulky separate shapes in the whiteness of the morning.

One of the pallbearers was trying to start a conversation about classic cars. He was bidding on a 1965 Triumph Herald convertible on eBay. It needed a lot of work and he was looking forward to its restoration. ‘Very unusual colour combination, olive and cactus. Last tax disc was 1979 so it’s been off the road a long time. I think there’s plenty of potential there for a lovely motor.’

His boss gave him a hard look. This chat was out of order.Poor woman, dead and buried to a threnody of leather interiors and nostalgia for string- backed driving gloves.

‘Come on now,’ he said, ‘someone loved her somewhere. Must have done. Show some respect.’

The pallbearer apologised but went on thinking about whether the paint was original.

‘You’d imagine so,’ said the priest, ‘yet here she is and it’s just the six of us, who don’t know her from Adam, not even her name.’

My name is Father Gerry Cutler, he thought, and over there is Kevin Redmond the undertaker with his professional AIDS ribbon, though there’s fewer of them dying now, thank heavens. That’s Geoff Stott, on his phone the whole time, and the others I’ve been introduced to but I can’t recollect what they’re called. All had families and friends who loved them and a wider circle than that. Father Cutler had his parishioners. The undertaker had many customers, if that was what you called the bereaved. It was the same for the others, he had no doubt; and this poor lady with no one, not a soul in all the world except for God who must have known her.

The day was ashiver. The sky looked sleety though it hadn’t yet started to rain. Miserable time of year. The Christmas lights were all gone from the shops and only the Easter eggs to look forward to.

‘Let’s get in to the warm, shall we?’ the undertaker said. ‘We’ve done all we can.’

They walked back in from the cold. He made a pot of tea and opened a packet of biscuits. ‘Help yourselves. Keep your strength up. Only gingers, sorry about that; we finished the last of the chocolate digestives yesterday.’

The door banged, letting in a blast of freezing air. The policeman arrived; icy drops glittered on his beard, his pale blue eyes gleamed in a worn face wrapped against the cold in a navy Crombie overcoat. He was heavy set, but not fat; he came in with the confidence of a man with a provable identity, no hesitation.

‘Blimey, did I miss it? I’m so sorry, just couldn’t find the place. I don’t know this part of London. Never even knew it was here.’

He introduced himself. Detective Sergeant Pete Dutton who had led the investigation. They were way out east at Manor Park by Wanstead Flats.

The drive had taken forever. The Thames rolled along from the soft Surrey hills under the fancier bridges, Richmond, Putney, Chelsea. Pete had set his alarm for six and went out with his Crombie overcoat collar turned up when everyone else was in bed. The streets were still black, there was little early traffic until he hit Chiswick High Road then it choked up. The coffee shops were opening, figures slinking in like wraiths under fluorescent lights. He had his own coffee in a flask.

‘Too late; she’s gone, I’m afraid,’ said the undertaker. ‘Wasn’t much to miss, to be honest. Just us.’

‘No one else turned up? I was hoping someone might have read that piece in the local rag and finally twigged.’

‘Not a living soul. Just the camera boys.’

‘What a crying shame. Seven months’ work and all over in five minutes.’

‘I know. Have a cup of tea, warm yourself up. There’s plenty of biscuits if you’re peckish; only gingers, though. Your gingers are the ones which always get left over, don’t you find? They’re not a popular biscuit, even the Rich Tea get eaten up quicker and they taste of nothing.’

To drive all this way and not even see her last moments, coming in from Surrey when he didn’t need to, not out of a sense of duty but a feeling – not even of respect, just wanting to be here, for he might be all she had in the world to worry about her and think about her and not let the matter drop though it wasn’t in his hands any more and nothing left to be done. He had seen her not long after she came out of the water. Six hours earlier she had been alive, walking through London. He felt once more the sharp, tearful resurrection of that distress he had felt when he had arrived at the incident and said, ‘What have we got here?’ He was looking down at her, drowned, mud- plastered, bruised by sea chains. Pretty only a few hours ago, blonde, slim, well presented, now something a dog dragged up from the water.

He drank his tea and ate a couple of biscuits. The others in the room were johnny- come- latelies. They had no idea about her. He had picked a red flower from the Christmas cactus by the television in the lounge at home, placed it gently in a freezer bag and transported it all the way across London with the intention of dropping it on to her coffin and now he’d lost his chance. Nothing to be done. The flower was in his pocket, he’d throw it in the bin. More waste.

‘Do you not think sometimes,’ the undertaker said, looking round the room for support from his colleagues for an idea he had always wanted to express in public but somehow never had the opportunity (the subject hadn’t come up, or not in the right way or at a time which seemed appropriate), ‘that throwing yourself off a bridge must seem quite seductive? The death it offers has a kind of grandeur. I don’t know, you could call it a return to the elements.’

‘Nah, I wouldn’t say that it was grand at all,’ said Geoff Stott, who had taken out his phone and was checking the bids for the olive and cactus Triumph. Still sluggish; this might be his lucky day. ‘Because if you think on it, there’s no one to see you do it. I mean, where’s the gesture that would get you noticed? If you wanted to go out with glory you wouldn’t just slip away like that.’

The starting point was not known. CCTV had first caught her near Moorgate station. They had searched for her image in the tunnels and on the escalators but she emerges out of nowhere past cliffs of pale implacable buildings, walking, walking, walking. By Mansion House, Bank of England, Old Billingsgate, St Magnus the Martyr, London Bridge. She had climbed on to the balustrade and thrown herself over unnoticed. Did she hover there? Could a passer- by have talked her down or did she go straight off? No witnesses had come forward. According to the pathologist she had been in the water five or six hours when she was found so it would have been around ten at night when she jumped, a time when transport was roaring through streets and

tunnels and people were coming out of theatres and cinemas and still eating in restaurants; the city was not bleak, it was engorged with pleasure. A warm night in July when people were moving from one gratification to the next, a veil of humid happiness lay over the good city.

‘Listen, let’s have a bit of reality here,’ said Pete Dutton. ‘She would have been dead in about six minutes. In fact, I’d be surprised if she lasted that long. My brother’s got a boat moored out at Teddington Lock. We’re river people us Duttons, grew up on it, Strand on the Green near Kew Bridge, Wind in the Willows kids, so I know quite a bit about the Thames and its peculiarities. Even on a warm day, and this was a warm day, or had been earlier, you’re struggling immediately, the fall itself completely knocks the wind and strength out of you, no matter how big you are or how young. And she was a female not some strapping lad who might swim his way out of trouble. Very soon you start to lose control of your arms and legs, the cold gets into you.’

‘Even on a warm night? It was very warm – humid high summer, if I recall,’ said Geoff Stott.

‘Oh yes, a few inches below the surface and it’s cold, the water isn’t stagnant, the tides are always running, you see. So knocking the wind out of you with the chilly water is enough to make you start drowning anyway, then you’ve only got to start taking one mouthful of water and it’s game over. So maybe not even as long as six minutes.’

‘Yes, that’s exactly my point, if you want to make a statement,’Geoff Stott said, closing down the eBay app on his phone, ‘you’d be better off throwing yourself under a train during the rush hour. Person on the line. Disruption on the track. All that temporary inconvenience. People late for job interviews, missing their connections, never turning up for a date. But she just slipped over the sides and no one saw her. You wonder if she changed her mind on the way down, tried to save herself but didn’t stand a chance.’

‘But why did they find her so quickly?’ said the priest. ‘You hear of people chucking themselves off and nothing is ever recovered, not a scrap of clothing even, doing a Lord Lucan.’

‘Yes, she was lucky,’ said Pete. ‘Or not, as the case may be, depending on what she actually wanted. Did she hope she’d be found? We’ll never know. In the early hours of the next morning they spotted her, I mean the river police patrolling for smugglers, it’s all drugs and bodies in that line of work. The poor woman only got herself tangled in the chains of HMS Belfast and that stopped her progress downriver.’

The others had seen the posters of her after she’d been cleaned up. The police forensic artist had carefully opened her eyelids for the colour of her eyes, to see whether they were dark or light, for that would make all the difference to the face and how he might make her appear as though she had once been alive. They were pale blue. He closed them again, pressing his finger against the ice- cold lid with brown lashes long cleansed by river water of any cosmetics, went to the sink to rinse his hands, thinking as he soaped them that whatever he did he could not capture her and that was partly his own failure being no Rembrandt and partly that something had gone, leaving the premises of her flesh vacated.

The undertaker had prepared her body after she had lain all alone in the freezer drawer like a long bag of peas so he had come very late to the case, as had all the others at the funeral apart from Pete Dutton who thought, What do they know or care despite their professional pieties?

It was all so bloody mysterious. Her clothes when they found her, everything down to the knickers and bra, were from Marks & Spencer. That wasn’t a particularly cheap shop, the company still prided themselves on quality; Pete Dutton bought his own undercracks from there, not shirts or suits or jeans, though. He had some self- respect, even at fifty- two he preferred something a bit more interesting; there were fantastic shops in Richmond if you knew where to look. Still, good old Marks & Sparks. It meant she was not a homeless person, not a vagrant, not a rough sleeper. The investigation had checked with the company, she was wearing jeans and a top which were in the stores a few months before. Her jacket was only a year older than that. Her shoes were Nike trainers with silver flashes. She had no tattoos and no rings or mark of a ring. Her ears were pierced but the holes were empty. Her light mousy hair was dyed with blonde highlights: not all that long ago applied, judging by the roots, three or four months’ growth. She had no money at all on her, let alone a wallet, nothing at all in her pockets.

Dutton explained all this to the others, who took it in with a lowering sense that the day could only get worse.

What is my connection to my fellow man? thought Geoff Stott. Is it no more than something at the end of my fingers, some pixels on my phone? And maybe he would not walk out of the room tonight into the kitchen to make a cup of coffee when his wife began her nagging about spending too much time with old cars and not enough time with people. But no, he would have forgotten by the time he got home, he knew he would. A leopard can’t change its spots. I like cars, he would tell her. They’re my thing. He hoped his wife would be the person to make sure they didn’t lead him to a bridge and water. She’d see him straight. And how long before I shake off this morning, this frozen corpse, this buried box, or will it stick around like a dirty toilet smell?

The radiators were warming up, they were reaching their temperature set point. The office by the chapel was cosy and the men ate more biscuits. Outside in the paupers’ graves the dead

were laid on top of each other until the hole was full and they started a new one. Below the ground lay blocks of wooden studio apartments each with their sole inhabitant. In death, maybe they kept each other company, maybe they had parties down there, bringing bottles from one coffin to another, lonely people finding sociability only when they were turning to compost.

‘What do you think happened?’ said Geoff Stott. ‘Who was

she? You must have your suspicions, clues, leads?’

‘’There’s always theories, of course there are.’

‘And?’

‘Not my case any more. Let’s see what the next round of publicity throws up. The camera boys are on it now. Fingers crossed.’

Outside the TV crew had been silent and respectful. They were still at the grave and had not joined the others for tea and biscuits. They filmed the digger at first from a distance; when the paltry funeral party moved off they came in closer. Beneath the ground the unknown woman was buried deep, like the victim of an air raid. She was London’s daughter now.

Pete Dutton went out and said hello to Alan McBride with his camera and crew. They shook hands. ‘Not as cosy as when we last met,’ Pete said. ‘You found it all right? I had a hell of a job, got lost, missed the interment.’

‘Sorry about that; it was terribly sad.’

‘I had a flower for her. I feel like a right pansy myself for getting so upset.’

‘Poor woman.’

‘I know. And nothing to identify her in death, not even now.’

‘There was something – a plaque on her coffin.’

‘What did it say?’

‘Just the date of her death and DB27. I don’t know what—’

‘Oh that, it’s not what you think. It just means she was the twenty- seventh dead body we pulled from the river last year. There were more, of course, as the year went on. Most quickly identified, reported missing, looked out for. We’re all a set of numbers one way or the other: National Insurance, credit cards, bank details, and all the rest they’ve got on you, but at least we’ve got names. She had one, don’t forget that, we just don’t know what it was.’

‘Thanks again for your help, thanks for everything. I really appreciate it, if it wasn’t for you—’

‘No, it was a pleasure. When’s your show going out?’

‘We haven’t got a transmission date yet; they’re talking about July, the anniversary. I’ll be in touch as soon as I hear.’

‘Let’s hope it jogs someone’s memory. You never know.’

‘I mean, it’s got to.’

‘Yes, you’d think.’

‘Would you mind if I filmed you for a minute or two walking towards the grave? Is that okay? Do you want to hold the flower?’

‘I think I’d rather chuck it if you don’t mind.’

‘Okay, whatever you feel comfortable with.’

Alan watched him march down the dead avenues. He was sorry the policeman had not arrived on time. He seemed the only human link in this unpeopled story. The fog was clearing,

the sleet was starting to make itself felt. Conditions for filming were difficult. It was hard not to be moved by the bleakness and poverty of her funeral, the indifference of its attendants.

When Pete had performed his walk, his hands in his coat pockets, feeling the dying flower encased in plastic, chucking it in a bin by the gates of the cemetery, angry with himself and her – her for being so conclusively lost, himself for being unable to make her not matter – he got into his car and drove west. The journey home was long. The sleet was definitely moving in from the north now. He passed along the A12, by Stratford and the Lee Valley Park, through Hackney into central London, braking for a few minutes by the site of the recovery of the body, looking out once more at London Bridge, undistinguished, concrete and steel, box girder construction and only forty- odd years old. An unromantic structure apart from its famous name. What made her do it here? The river was black and cold today. It seemed scummy and foetid. Along the bottom were the bones of sailors and of fallen women. Hardly anyone knew of Dead Man’s Hole, the old mortuary where they kept the bloated corpses of the suicides pulled from the river. He had seen the long pole, the row of hooks. The sight sickened him. Had she known . . . ? But maybe the undertaker was right and the glamour of the plunge, the exhilarating drop, had drawn her. How decisive it was, death was certain.

It was his river. Now she was its property and so she was also his. It was beyond his ability to explain to anyone. It was his secret. He had talked about the case while it was his case, but when it ceased to be there was no longer any reason. She lodged herself inside him. She had become a part of his life. A shrink would want to get to work on that and ask him a load of

questions he’d struggle to answer except to say, Well, you know, something had happened, I was already poleaxed, and she just turned up. And was it disloyalty to his wife? How could you two- time a living woman with a dead one?

He gave up the struggle to work it out, he wasn’t a deep thinker, things were churning, which was to be expected in the current circumstances. Slipping the brake, he drove on, passed through the West End, skirted Buckingham Palace, drove down Brompton Road. In Chiswick he stopped for a late breakfast.

Alone at his table he ate bacon, sausage, egg and chips and wondered how long this would go on, the dreams he woke up from with a sudden rush of longing to return to sleep, and to her. Who can you talk to about such matters? No one, you’re not that kind of guy, unless HR spotted his odd demeanour and sent him for counselling. So you keep it to yourself, go to Sunday lunch with the in- laws once a month, bid for punk- era badges and other paraphernalia on eBay, go shopping in the West End, thinking back to your youth and how there’s no one braver than a teenage working- class dandy in the age of punk with a few quid in his pocket to spend on clobber and records. The shirts he used to have! The beautiful shirts, the reckless T-shirt slogans, the Doc Martens, the drainpipe jeans.

In the dream world there she is, though she had lain for so long, freezing cold in the morgue, naked, her M&S outfit in a plastic bag in storage. A body in waiting. Now she is buried and it is over until she comes staring blindly out of a TV screen and someone says, Look, it’s her.

All he can do is wait. Go home to a sick wife and be a cheerful face around the house, filling the dishwasher and emptying it, all the weary routine while Marie, upstairs, tries her very best to get better, giving it her all, all for life and for living.