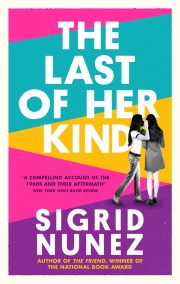

Q&A with Sigrid Nunez

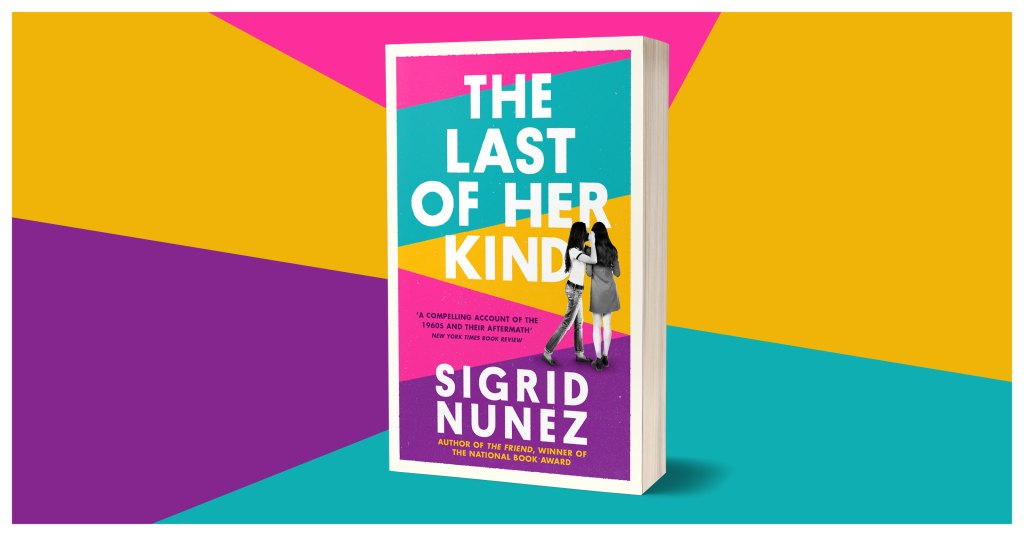

SIGRID NUNEZ ON THE LAST OF HER KIND

Sigrid Nunez, author of The Friend chatted to us about reissuing her novel The Last of Her Kind, a haunting and provocative novel about female friendship, 1960s counterculture, race, class, politics, idealism, violence and protest.

Q: Some readers might think The Last of Her Kind follows a particular trope in literature – that of telling the tale of an extraordinary person’s life through the eyes of a more relatable friend (like in The Great Gatsby, or more recently, The Secret History). But it does set itself apart in George, who is more characterful than those typically featured in this category. Did this occur to you when writing and did you deliberately give George more agency?

A: From the beginning I knew I wanted the story to be told by someone who was an astute observer and chronicler of her times but who stood at a certain remove from events rather than at the heart of them. George is far less extraordinary than her friend Ann— as she is less extraordinary than her sister Solange—and her take on their lives is largely that of a subjective but reliable witness. But I did also want George to be a strong and engaging character and to show how the era in which she came of age shaped the woman she became. That she’s the one who’s doing the work of looking back and searching for the meaning of it all makes her, for me, the novel’s most important character.

Q:The novel is George’s way of putting her friend on trial. You introduce early on the hint that Ann commits a crime, and lead the reader slowly through the back story, to the act itself and then the aftermath. Do you invite judgements from the reader, or prefer they will judge the society around these young women?

A: I don’t think it’s necessary for a reader to take one side or the other. There are moments when the reader will judge the characters as individuals and other moments when they will judge the society—and the families—that they come from.

Q: Salon wrote in their review that ‘a writer of Nunez’s piercing intelligence and post-feminist consciousness may well feel that writing the Great American Novel is no longer a feasible or worthwhile goal—but damned if she hasn’t gone and done it anyway.’ What do you think The Great American Novel actually is – and if it exists, is it still relevant? In your mind, what should it be?

A: The Great American Novel always seemed to me to be something that certain Great Male Narcissists obsessed about. No one seemed to think such a book would or could ever be written by a woman. I don’t think many people take seriously anymore the idea that there is such a thing as a Great American Novel or that this is what an American novelist should be aiming for.

Q: When George’s sister Solange returns in the second half of the novel it’s as if she’s risen from the dead – from the morgue photos and George’s fears and grief – into startling, vivid life with her tales of hippie freedom. Did you use her to complete the portrait of America at this time? Why was it important to you to show not the adventurous life she led, but the way she was afterwards?

A: Solange represents a type of person that was very common at the time: the hippie girl/groupie. I found her story interesting to explore in itself, but I wanted to use the sibling relationship to help develop George’s character as well. Also, The Last of Her Kind is not only a story about a friendship but also a story about a family, and Solange turns out to be the family member with whom George has the closest relationship over the years.

Q: ‘One single, endless, smoky conversation…’ The Last of Her Kind could be described as George telling her side of the conversation that makes up her friendship with Ann. You do something similar in The Friend, which is written in second person to the narrator’s best friend who has recently died. What rules, freedoms and restrictions do you find in telling ‘one side’ of a fictional relationship?

A: In fact only certain parts of The Friend are addressed to the narrator’s dead friend. Most of the book is straightforward first-person narrative. As a novelist I’ve been drawn to a kind of hybrid form that presents itself as part autofiction, part fictional biography. There is a narrator—a female writer—who tells the story of the lives of one or more persons she has known. I used this form for my first novel, A Feather on the Breath of God, and I seem to keep returning to it, so clearly it’s a form that works well for me.

Q: ‘For all the time I wasted on you! You unteachable — hopeless — you stupid, stupid —’ Ann’s outburst hints that her only motive in friendship with George was self-righteously pedagogical, a project of reform. Like her romance with Kwame, it raises suspicions. In your portrait of Ann, is she incapable of truly equal relationships? How do you feel about her as a character?

A: I don’t agree that Ann’s only motive in friendship with George was pedagogical. During their time together at school, these two women develop a very serious, complicated, and loving relationship. But, like so many other youthful relationships, with time it cools and dies. And others may have doubts about this, but I believe Ann truly loves Kwame, though whether or not that love would have endured we’ll never know. As for my feelings about Ann’s character, I have great respect for her. I think, in the end, for all her terrible flaws, she is a noble and even heroic character. How many people stay true to their ideals throughout their entire lives, no matter what hardships and sacrifices are required? Think of it this way: if a lot more people were like Ann Drayton, would this be a better world, or a worse one? I think you’d have to say a far better one.

Q: There’s a crackling brilliance to your descriptions: ‘a profile like a hatchet . . . with her long, thin neck for the handle,’ especially when writing about acid trips. Were you inspired by the music and literature of drug use from the sixties and seventies and was it fun to play with the narrative form as George gets high or breaks down?

A: I used my own experience using LSD and other drugs to write those scenes, which were indeed great fun to write. I’d always wanted to write about an acid trip because it’s such an unusual and vivid experience, and of course most people have no idea what it’s really like.

Q: I wish I were black.’ The novel was published in 2006, set from 1968 onwards. Since then, there have been more complex conversations about benevolent racism and highly publicised controversies such as the outing of Rachel Dolezal. Do you think readers now will view Ann in a different way to when you first published it?

A: Readers past a certain age will remember how common it was back then for white people to say, as Ann does, that they wished they’d been born black. I heard it on campus all the time, as I often heard “I wish I’d been born poor.” It was also common for white members of the counterculture to see themselves as a marginalized and often abused group and to take that as a reason to identify as “black”. This might strike many people today as both bizarre and deplorable, but we’re talking about a time when Senator Robert Kennedy saw nothing wrong with publicly announcing that he wished he had been born an Indian.

Q: Writers often say it’s hard to let go of a book, or that it’s never finished. How does it feel to have a novel re-issued in the UK thirteen years later? Do you find yourself reconsidering it, or are you content? Is there anything you’d change if you could?

A: I’m like most writers: I reread my work and all I can see are the flaws. I can’t imagine ever being content with anything I’ve written. There are always things in a book that could have been done better. But, needless to say, it’s a thrill to think of this novel reaching an audience in the UK after all these years.

The paths of two women from different walks of life intersect amid counterculture of the 1960s in this haunting and provocative novel from the National Book Award-winning author of The Friend

It is Columbia University, 1968. Ann Drayton and Georgette George meet as roommates on the first night. Ann is rich and radical; Georgette is leery and introverted, a child of the very poverty and strife her new friend finds so noble. The two are drawn together by their differences; two years later, after a violent fight, they part ways. When, in 1976, Ann is convicted of killing a New York cop, Georgette comes back to their shared history in search of an explanation. She finds a riddle of a life, shaped by influences more sinister and complex than any of the writ-large sixties movements. She realises, too, how much their early encounter has determined her own path and why, after all this time, as she tells us, 'I have never stopped thinking about her'.

'A brilliant, dazzling, daring novel' Boston Globe

'A subtle and profoundly moving novel about friendship, romantic idealism and shame' O, The Oprah Magazine

'An unflinching examination of justice, race and political idealism that brings to mind Philip Roth's American Pastoral and the tenacious intelligence of Nadine Gordimer' New York Times