Read and Extract from The Virago Book of Witches

Preface

The witch: resilient, edgy, awe-inspiring and potent. She never disappears from our culture for long. Iconic celebrities such as Björk and Ariana Grande have claimed an association with Wicca. Witches strut the catwalk with wide-brimmed hats, wearing sultry expressions and dark, strangely haunting tatters or dressed in startling ball-gowns heightening their shadowy mystery. Photographers have made artworks featuring women in gothic make-up and tangled hair against bleak, grey and black landscapes. The witch has even been used to advertise shelves and cabinets laden with jars and amphora suggesting the ancient craft of brewing healing potions, love philtres and spells for success or punishment. Tarot reading and charm-infused gems and crystals are all popular once more.

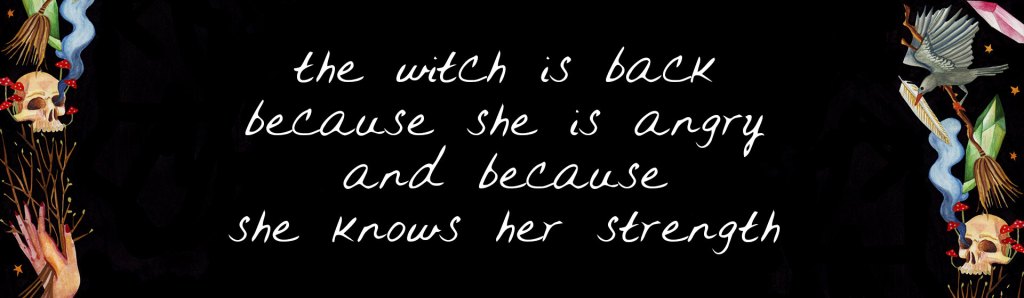

Today’s resurgence of interest in all things witchy tells me that she’s with us again for a reason. It’s not just that the sheer versatility of her character lends itself easily to fiction in books and on screen, and even in the lyrics of contemporary music. No, the witch is back because she is angry and because she knows her strength.

Fierce independence has always dominated witch stories, so it is no surprise that the archetype of the witch has gained new popularity among a generation of women seeking to express their autonomy.

The spirit of the courageous, if sometimes foolhardy, reactions of women accused of malicious witchcraft in the early modern period, I believe, has provided a release today for the long-forbidden anger of women. The history and folklore of witches can tell us about the marginalisation and resistance of contemporary women.

The flood of anger expressed by so many of us for the past and present inequalities we have faced at home and in the workplace, chimes for me with the long, drawn-out and dark experience that women accused of witchcraft underwent between 1450 and 1750. Widely known as the Witch Persecutions, these took place all over Europe and America in a period when people still believed unquestioningly that the Devil was present among them. Over the years stories of women consorting with the Devil have leaked into folklore and poetry and art. In my section on Witchy Devices, and elsewhere in this collection, is a small sample of stories featuring the anarchic energy, frolics and humorous escapades of witches, but even when the tales are full of fun and silliness, the aura of the desperately brutal ‘Burning Times’ lurks in the background. The Malleus Maleficarum, (Hammer of the Witches), a text produced in 1487 by the German churchman and subsequent inquisitor Heinrich Kramer, focused its overt misogyny on the malevolence of witches and for two hundred years sold exponentially throughout the Christian world, coming second only to the Bible. During three hundred years of the persecution and murder of women, witch hunters were encouraged by the highest authorities of Church and monarchy to interrogate and sentence witches for the most bizarre and trivial reasons. Between thirty-five and a hundred thousand people were executed, at least 80% of whom were women. Accusations of a huge, unnatural appetite for sexual activity, perverse sexual acts with the Devil or attacks on the virility of men almost always played some part in the trials. The murdered women were primarily downtrodden, uneducated and often too ignorant to understand the complexities of religious change during that period. But despite being helpless and in danger, the women spoke out, shouted back, stood up to their ‘superiors’ and defied the authorities who accused them of using evil magic to blight crops, sour milk, make men impotent and children sick. They went to their death – drowned, hanged or burned – usually for an act of defiance or self-ill. Obsessive and hate-fuelled persecution based on a confusion of religion, property ownership, authority, professional jealousy and politics came to be focused on a group of women. Women who, though foul-mouthed, defiant and sometimes verbally abusive, were essentially harmless.

The last century has seen significant progress towards the independence of women, but damaging traditions remain, and have been internalised, even by women themselves, and certainly by society. Consider some witch-related terms directed at angry women; banshee (a howling night- witch and harbinger of death), she-devil (Lilith and her daughters), bitch (associated with Hecate, the ancient Witch- goddess whose chariot is drawn by dogs). The method of persecution in those dark times is of course in no way comparable to the experience of women today, but the suppression of women who dare to defy social norms still resonates in the subsequent responses – sexual harassment, violence and bullying in the workplace – that violate the self-respect and human rights of women and has a deep emotional effect.

It is likely that the answer to the historic, obsessive persecution of witches lies in the psycho-analytical concept of ‘projection’, a process through which people disown the qualities they find undesirable in themselves and seek to impute their shortcomings to others. The dishonest doubt the honesty of others. The indiscreet believe others can’t be trusted with discretion. Those who wish to seize control fear being controlled. Those who project, while exonerating themselves, attribute a level of power to the ‘other’ which exists only in their own mind. Jung called this rejection of one’s own flaws the shadow – ‘that which I do not wish to be’. Few of us are so self-aware that we can claim to know or own all our weaknesses and the tendency to project spreads through society. In private interactions it becomes a blame game between individuals but collectively, societies identify a group which they believe contains the darkness. Sometimes it is an unconscious act. When superstition was rife, and small acts could result in torture and execution, these instances of self-hate and denial became intensely focused on the defenceless, the other, the outsider. Witches are perhaps the most infamous and long-lasting example of such groups but the projection of evil on to ‘the other’ still goes on.

In keeping with the theory, the very characteristics that the persecutors pinned on so-called witches could be easily demonstrated in themselves: lack of rationality, torture, cruelty, greed, bloodlust and perverse sexual acts.

Over-sexualised women who deplete the potency of men, abound in folklore and legend with stories like that of Ala and the Hag, from the Congo or The Painted Skin, a story from Japan about a dying or dead woman tearing the throats of men to draw out their vitality. In places that fear women and feel the need to dominate them it hasn’t gone away. It resonates through society today – on the factory floor, in boardrooms, on casting couches and in production offices. Even the halls of political power are not sacrosanct – protest is silenced with denials, mockery, accusations of lying and warnings of ‘ruined’ careers. If one of us stands up to harassment, particularly sexual assault or coercion, we risk being defined as difficult, a battle- axe, a troublemaker, a liar or blackmailer – or of course, a witch.

The suppressed frustration and rage of not being heard, simmering in modern women for decades, has finally boiled over. But where the victims of the early modern period, being illiterate, were unable to refute their so-called confessions, women today are ripping up their non-disclosure agreements and staking their all to expose the misdemeanours of the establishment. The reversal has been described as a ‘witch-hunt’ by some of the accused and even the not yet-accused. No one believed them – the witches are being avenged.

To me the witch is the ultimate example of womanhood in all its complexity. Her stories await in the pages of this book. A celebration of anger, tomfoolery, fun, strife and victory! We have not forgotten. We salute her.

Shahrukh Husain

London, 2019

The Virago Book Of Witches

by Shahrukh Husain

A collection of more than fifty stories about witches from around the world. There are tales of banshees, crones and beauties in disguise from China, Siberia, the Caribbean, Armenia, Portugal and Australia. The characters featured include Italy's Witch Bea-Witch, Lilith, Kali, and Twitti Glyn Hec. Alluring women, enchantresses, wise old ladies and bewitching women: they are all here and ready to haunt, entice, possess, transform, challenge - and sometimes even to help.