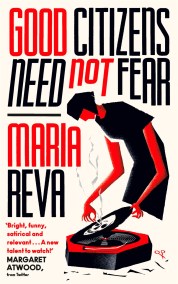

Writing from Curiosity, Not Rage by Maria Reva

My family and I emigrated from Ukraine to Canada in 1997. My sister, twelve years old at the time, couldn’t wait to leave. Browsing my aunt’s German toy catalogues with their glossy tableaux of happy children at play, she’d lament being born in the wrong country. As for me, I was seven and wanted to stay. The English-speaking world seemed hostile; I associated it with the evening language classes my mother dragged me to every week. Due to the rolling blackouts, we’d often have to navigate pitch darkness, treading carefully to avoid slipping on icy cement.

Fortunately, Canada proved to be less treacherous than I’d anticipated. Street lamps turned on every evening and worked through the night, dutiful as guards. Teachers hardly yelled at students. Strangers smiled at each other, and even the cats seemed friendlier. As I settled into our new life, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I had a double in Ukraine, the girl who stayed behind. In fact, I still think about her. She is horribly shy, afraid to cross crowded hallways. She works a practical job, with which she may be perfectly content. She has never considered a lofty thing like writing.

I kept thinking on this – how life would have been different, had we stayed – when I wrote Good Citizens Need Not Fear. ‘Lucky Toss’ explores the resurgence of religiosity when the promise of a happy communist future disappeared. ‘Roach Brooch’ deals with the breakdown of the traditionally close-knit grandparent–grandchild relationship.

Moreover, Good Citizens allowed me to delve into the world of my parents’ and grandparents’ generation. The first story I wrote for the collection, ‘Novostroïka’, was inspired by a lunchtime conversation with my parents. They recounted how, due to a clerical error, our panel building in Ukraine hadn’t made it into the city’s registry. None of the municipal services recognised the address, instead informing my parents that it was impossible to connect heating to a building that didn’t exist. If an entire building is ‘without papers’, I wondered, what happens to the people living inside it? If you are repeatedly told that something does not exist, when do you start believing it?

The challenge of writing Good Citizens Need Not Fear was to avoid making it flatly anti-Soviet. Like millions of other citizens of the former Soviet Union, my family carries intergenerational anger. We lost relatives, land, career prospects. My grandmother had to flee Ukraine during the 1930s famine. We were made to believe that Ukrainian culture was inferior to that of Russia (my sister and I grew up thinking that Ukrainian wasn’t a language in its own right, but a corrupt version of Russian). While conducting research for the story collection, however, I had to recognise the fact that Soviet nostalgia persists, even among expatriates. Svetlana Alexievich’s Second-Hand Time features many interviewees who reminisce about what they call a simpler life. At least everyone was guaranteed a job, the interviewees argue – that the job paid little didn’t matter, because there wasn’t much to buy in the stores anyway. Money didn’t determine a person’s worth, as it does now. The years of economic turmoil that followed the collapse of the Union hardly showed capitalism as a better alternative. I thus sought to write Good Citizens Need Not Fear out of curiosity rather than rage. Writing is an exercise in empathy; I had to embody that nostalgia myself. Who believed in the communist system? Who thrived in it? The two aren’t always the same.

'Bright, funny, satirical and relevant. . . . A new talent to watch!' MARGARET ATWOOD (via Twitter)

'Bang-on brilliant' MIRIAM TOEWS

This brilliant and bitingly funny novel-in-stories, set in and around a single crumbling apartment building in Soviet-era Ukraine, heralds the arrival of a major new talent.

'A comic triumph' GLOBE AND MAIL

A cast of unforgettable characters--citizens of the small industrial town of Kirovka--populate Maria Reva's ingeniously entwined tales that span the chaotic years leading up to and immediately following the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989. Weaving the strands of the narrative together is an unforgettable, chameleon-like young woman named Zaya: an orphan turned beauty-pageant crasher who survives the extraordinary circumstances of her childhood through a compelling combination of ferocity, intelligence, stubbornness and wit.

Inspired by her own family's history, Reva's Good Citizens Need Not Fear takes us from paranoia to tenderness and back again, exploring what it is to be an individual amid the roiling forces of history.

'Luminous' YANN MARTEL

'Outstanding' ANTHONY DOERR

'Maria Reva's enthralling debut of interlinked short stories achieves the double effect of timelessness and timeliness' KAPKA KASSABOVA, GUARDIAN BOOK OF THE DAY