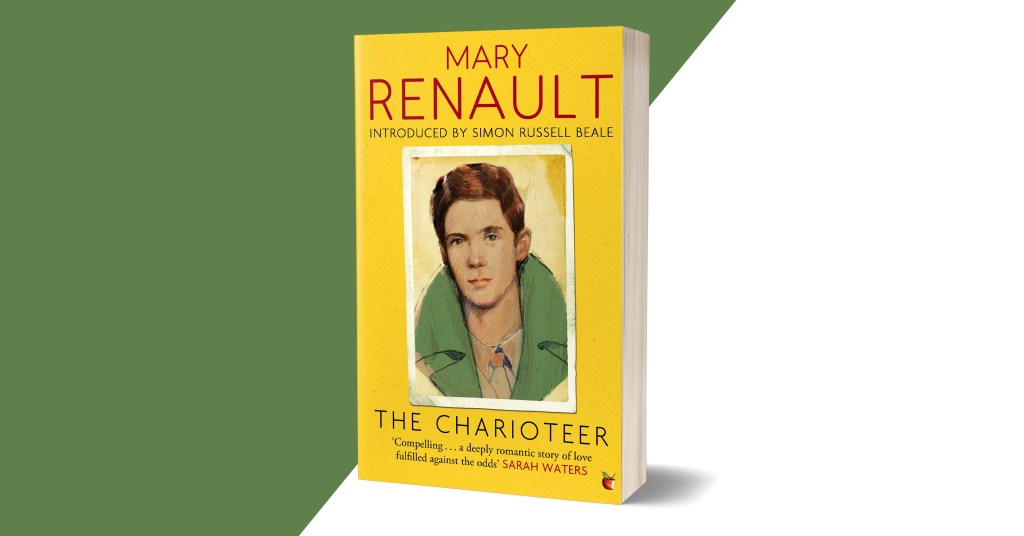

Pride 2020 | An Extract from Mary Renault’s The Charioteer

In the first of our Pride 2020 extracts, discover The Charioteer by Mary Renault. First published in 1953, The Charioteer is a tender, intelligent coming-of-age novel and a bold, unapologetic portrayal of homosexuality that stands with Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar and James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room as a landmark work in gay literature.

‘The Charioteer remains compelling both as a snapshot of a particular – and particularly fascinating – cultural moment, and as a deeply romantic story of love fulfilled against the odds. It has all those qualities that make Mary Renault so memorable as a novelist: craft, subtlety, intelligence, and a terrific natural sympathy with the intricacies of honour and desire’ SARAH WATERS

‘An explosive and courageous book’ SIMON RUSSELL BEALE

* * *

Lanyon seemed about to step forward; and Laurie waited. He didn’t think what he was waiting for. He was lifted into a kind of exalted dream, part loyalty, part hero-worship, all romance. Half- remembered images moved in it, the tents of Troy, the columns of Athens, David waiting in an olive grove for the sound of Jonathan’s bow.

Still watching him, Lanyon made a little outward movement.

He paused, and drew back.

‘To give them their due,’ he said, his voice suddenly light and crisp, ‘dirty old men know one or two quite material facts. Incidentally, they’re quite material facts themselves.’

Laurie listened with his eyes. This time there was no need to answer.

‘You’ll be taking this study over yourself,’ said Lanyon in a busi- nesslike way, ‘in course of time.’

‘Who? Me?’ said Laurie, startled.

‘Obviously. Who else is there? I expect Jeepers will give you a frank little talk the first evening of term. Watch him carefully while he does it, and you’ll learn a lot. It’s not very edifying and rather a bore. However. Oh, just a minute.’

He turned and went over to the wooden book-box that stood in the window. Instinctively Laurie followed him, and looked over his shoulder. Lanyon straightened abruptly; his light, fine hair flicked across Laurie’s cheek.

‘Get out of the light: d’you mind?’ ‘Sorry.’

‘I’m just looking for something. Oh, yes, here it is.’ He stood up with a thin leather book. The spine said The Phaedrus of Plato. Laurie hadn’t got much beyond selections from Homer. He thought Lanyon, in this practical mood, was bequeathing him a crib.

‘Read it when you’ve got a minute,’ said Lanyon casually, ‘as an antidote to Jeepers. It doesn’t exist anywhere in real life, so don’t let it give you illusions. It’s just a nice idea.’

Laurie was strongly aware that as he took it their hands had touched. He said, ‘I’ll always keep it. Thank you.’

‘It’s a pity you and I couldn’t have talked a bit sooner.’ Laurie looked up from the book. ‘I wish we had.’ ‘Well,’ said Lanyon briskly, ‘it’s too late now.’

Laurie continued to look up at him. With a feeling of great strangeness and astonishment he knew that they were no longer the head prefect and a fifth-former, but just two people in a room.

‘Is it?’ he said.

Lanyon sat down on the edge of the table, looked at Laurie, and shook his head. ‘Spud,’ he said quite gently, ‘you mustn’t be difficult.’

Laurie didn’t answer. He felt like someone who tries to read a book when the pages are being turned a little too quickly.

‘I’ve been watching you,’ Lanyon said, ‘for a long time. You’re on the way to being something, and I don’t know what, not for certain. So I’m not going to interfere with it.’

‘I don’t know,’ said Laurie slowly. ‘I feel as if you had already.’ Lanyon smiled at him and he had to look down.

‘That’s only because you don’t know what it’s all about. Look, if you want to know, one reason why not is because it would mean too much. To me, too, if that’s any satisfaction to you. Anyway, no. Too much responsibility.’

‘I can take my own responsibility. I’m not a child.’

‘That’s what you think. Stop making such a bloody nuisance of yourself.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘It’s all right. You’ll see the point of all this later.’

Laurie turned and looked out of the window. He couldn’t think what had come over him. Lanyon had taken it pretty well.

From over by the fireplace, Lanyon said, ‘No good getting ideas, Spud. It doesn’t get you anywhere. It’s all just a myth, really.’

Presently Laurie said, ‘What are you going to do? After you leave, I mean?’

‘Merchant seaman.’ He spoke with the effortless-seeming deci- sion he might have used on a matter of House routine. ‘I’m going straight down to Southampton tomorrow.’

‘Are you all right for money?’ It was strange to feel so natural about asking Lanyon a thing like this. ‘I’ve got about a pound I could lend you.’

‘No, thanks. I can get a ship quite quickly. I know a man who’ll fix me up.’

‘Oh,’ said Laurie flatly. ‘That’s all right, then.’

‘We ran into each other. He’s not so bad. I don’t know him very well.’

Suddenly they had come to the end of all that there was to say. ‘Well, I’d better finish packing,’ Lanyon said. He looked at Laurie, telling him to go. Laurie stared at him, mutely; but there wasn’t anything one could say. Lanyon said, briskly, ‘Take these lists on your way down, will you, and pin them on the board. The

usual order. You know how they go.’ ‘Yes.’

‘That’s all, goodbye. What is it, then? Come here a moment . . . Now you see what I mean, Spud. It would never have done, would it? Well, goodbye.’

‘But when can we—’ ‘Goodbye.’

After a moment Laurie said, ‘Goodbye, Lanyon. Good luck.’ ‘I don’t believe in luck,’ said Lanyon as they parted.