The Landscape of a House by Chia-Chia Lin

I’m often asked about the southcentral Alaskan landscape in The Unpassing – the spruce forests, the sparse coasts, the long summer days, the beached whale. The outdoor setting offers solace to the characters, but it is also at times unforgiving, a land that in its vastness underscores their aloneness. But the truth is I’m equally interested in life indoors, the walls, how we maintain our homes or allow some amount of disrepair, and how the interior landscape of a house can be a frightening setting as well; the presence of other human beings is not only deeply felt, but sometimes inescapable. And what does it do to us to be contained?

Now, approaching four months of COVID-19 lockdown, with our son home from preschool and our family fortunate enough to still be sheltering in place, I can’t help but feel pulled back into the years when I was writing my novel, contemplating the ways that the details of a home reveal the state of a family, or mark the passage of time or a particular epoch.

The interior landscape of my own small, 730 square foot home has changed. Starting in early March, a newly scribbled coloring page was taped to our living room walls each day – like notches for the days of our confinement – until we ran out of walls. The floors have acquired new, long scratches as my son rides his big plastic train back and forth, back and forth, between the kitchen and the living room, all the while pretending that he is out in the world, buying pizza or grocery shopping or any number of painfully ordinary tasks. There are marks on the door where he rams the train right into it, and I can’t help but attribute meaning to it, the way he hits this closed door so hard. Is it my imagination, or is the paint all over our house chipping faster? As we live our narrowed lives in this space every minute of every day without break, I imagine that our home has aged a full year (as, perhaps, we have) from the sheer sustained intensity of our living.

Our refrigerator, crammed full of weeks’ worth of groceries, opened dozens of times a day, finally gave up and died, followed shortly by our freezer. We were slow to replace these rather necessary items. For a month, my husband ran out for ice every evening, as though we were living in the late 1800s, and we caught the steady rivulets of melting ice with a pile of rags. If a doorknob fell off right now, I would probably hide it in a closet. If the stove broke, I would lie down on the floor and not get up.

But all the same, the changes in our house amount to a strange comfort. In a time when it feels as though I am accomplishing nothing – only watching my son, day after day, often forgoing the work that in the past has challenged and sustained me – it can seem that each day simply vanishes without a trace. That my life is continually on pause. And so it does offer a fragment of comfort to know that these days do leave their mark – pasted, imprinted, dented and scratched into the various layers of our home.

The family in my novel lives in a narrow, rickety house on the edge of a forest. Nature pushes in; there are ceiling leaks during rainstorms, flying squirrels in the attic and mushrooms sprouting in the bathroom. The family’s presence is felt in the house itself, from the makeshift furnishings to the failed home repairs. Early on, the narrator describes figure-eight gouges on the floor where furniture had rolled like marbles during the big 1964 earthquake. I felt, back when writing these descriptions, and I’m reminded now, that there is something affirming and consoling in the way that our homes track, and hold onto, the changes and upheavals of our lives.

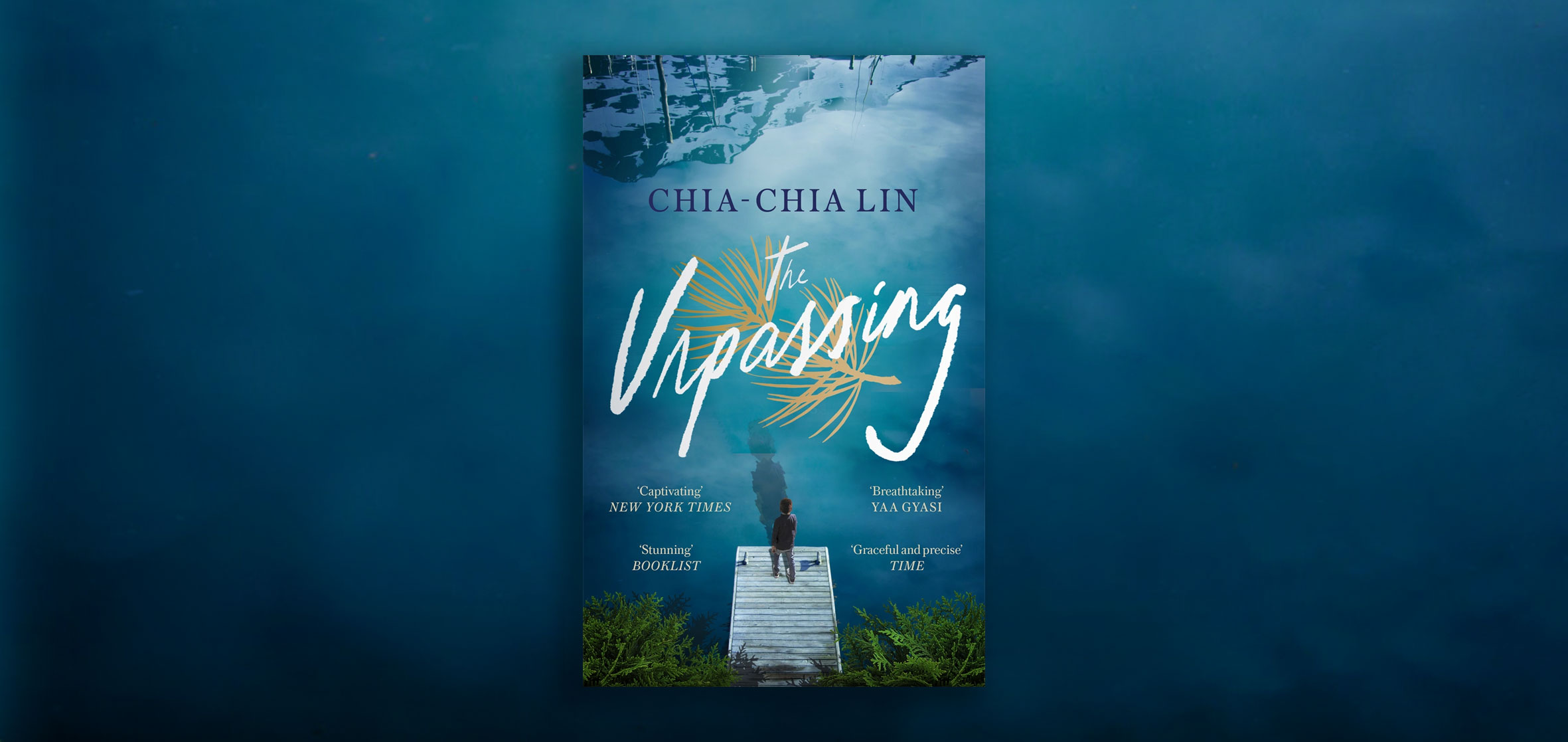

Read The Unpassing:

A major US debut novel in 2019

Shortlisted for the Centre for Fiction First Novel Prize

A New York Times Book Review Editors' Choice

In Chia-Chia Lin's piercing debut novel, The Unpassing, we meet a Taiwanese immigrant family of six struggling to make ends meet on the outskirts of Anchorage, Alaska. The father, hardworking but beaten down, is employed as a plumber and contractor, while the loving, strong-willed, unpredictably emotional mother holds the house together. When ten-year-old Gavin contracts meningitis at school, he falls into a deep, nearly fatal coma. He wakes a week later to learn that his younger sister, Ruby, was infected too. She did not survive.

Routine takes over for the grieving family, with the siblings caring for one another as they befriend the neighbouring children and explore the surrounding woods, while distance grows between the parents as each deals with the loss alone. When the father, increasingly guilt-ridden after Ruby's death, is sued over an improperly installed water well that gravely harms a little boy, the chaos that follows unearths what really happened to Ruby.

With flowing prose that evokes the terrifying beauty of the Alaskan wilderness, Chia-Chia Lin explores the fallout from the loss of a child and a family's anguish playing out in a place that doesn't yet feel like home. Emotionally raw and subtly suspenseful, The Unpassing is a deeply felt family saga that dismisses the myth of the American dream for a harsher, but ultimately profound, reality.

'A singularly vast and captivating novel, beautifully written in free-flowing prose that quietly disarms with its intermittent moments of poetic idiosyncrasy' New York Times Book Review

'A striking debut by an unforgettable new voice' Cosmopolitan