Why are folktales timelessly appealing?

The folktales of the British Isles tell stories of strange desires and troublingly alluring figures. They dig up remnants of old beliefs and patrol the shadowy borderlands between life and death.

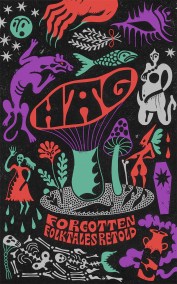

Folktales seize us with their strangeness and grip on tight, but why do we find them so timelessly appealing? We asked the authors of Hag: Forgotten Folktales Retold, to tell us why they think folktales have such power over us.

We talk often about what took place on a given spot in the past, or what will be in the future, but folktales are not now or later but parallel, running alongside and through our own lives. They remind us that we humans don’t have sole dominion over our world, that we are foolish sometimes, and destructive, and cruel: that we are blind to magic but also to one another. I’ve always enjoyed tales of tricksy, equivocating spirits who lead silly humans astray, but when I read the story of Old Farmer Mole, which inspired my contribution The Holloway, what struck me was that the supernatural is not always cruel. Sometimes it is just. Folktales assure us that something larger and clearer-eyed than us is at work, and it can put right our petty wrongs.

Imogen Hermes Gowar

The Holloway

I’ve always loved how folktales weave the ordinary and magical world together. Fairytales can often feel out of reach; this happened to a princess in a castle far away. But with folktales there is a commonplace, local element; this happened to a miller up the lane. I imagine when these tales were originally told, combining sprites, giants, merfolk (and in the case of my tale, a panther) within the local setting would not only have made it feel as if these things could happen, but they could happen to you. In the modern era, retelling these stories has a particularly alluring appeal as elements that were often excluded in the original versions – the point of view of women, for example – can add extra layers previously missed. Within every folktale there is a warning, and it’s interesting to see how these elements can differ when written from different perspectives as well as what elements remain the same. But essentially it is the magic within the ordinary that I feel we are drawn to and can look out for in our own lives, no matter what our age.

I’ve always loved how folktales weave the ordinary and magical world together. Fairytales can often feel out of reach; this happened to a princess in a castle far away. But with folktales there is a commonplace, local element; this happened to a miller up the lane. I imagine when these tales were originally told, combining sprites, giants, merfolk (and in the case of my tale, a panther) within the local setting would not only have made it feel as if these things could happen, but they could happen to you. In the modern era, retelling these stories has a particularly alluring appeal as elements that were often excluded in the original versions – the point of view of women, for example – can add extra layers previously missed. Within every folktale there is a warning, and it’s interesting to see how these elements can differ when written from different perspectives as well as what elements remain the same. But essentially it is the magic within the ordinary that I feel we are drawn to and can look out for in our own lives, no matter what our age.

Mahsuda Snaith

The Panther’s Tale

Folktales are skeletons of history that are passed through the ages, dressed in wondrous clothes to appeal to modern story lovers and all the while, their dark truths fester underneath and float on. Our timeless fascination with the macabre, the impossibility of folktales emerging as possible, plausible incidences ensures that the bare bones of these stories will always find their way into our consciousness.

Emma Glass

The Dampness is Spreading

One of the things that appeals to me most about folktales is their deep connection to local histories of place and landscape. When the Yorkshire folktale, Aye, We’re Flittin’, was shared with me, I was reintroduced to the word ‘boggart’. I’d encountered this word in place names in the north of England—the Boggart Stones on Saddleworth Moor, and Boggart Hole Clough in Manchester, for instance. I’d known these boggarty places, but I’d never heard the associated tales of boggarts tormenting households. I decided to set my own tale on the moortops of the Calder Valley, an area that has a long association with boggarts. Working with this tale enabled me re-visit and write about a place that I know well with a new aliveness to its past.

One of the things that appeals to me most about folktales is their deep connection to local histories of place and landscape. When the Yorkshire folktale, Aye, We’re Flittin’, was shared with me, I was reintroduced to the word ‘boggart’. I’d encountered this word in place names in the north of England—the Boggart Stones on Saddleworth Moor, and Boggart Hole Clough in Manchester, for instance. I’d known these boggarty places, but I’d never heard the associated tales of boggarts tormenting households. I decided to set my own tale on the moortops of the Calder Valley, an area that has a long association with boggarts. Working with this tale enabled me re-visit and write about a place that I know well with a new aliveness to its past.

Naomi Booth

Sour Hall

Apparently my grandfather heard the banshee cry the night my grandmother died. So, as a child, fairytales marked the places reason couldn’t go and explained shivers down the spine. Now, I think they let women go into the dark and sometimes return intact.

Apparently my grandfather heard the banshee cry the night my grandmother died. So, as a child, fairytales marked the places reason couldn’t go and explained shivers down the spine. Now, I think they let women go into the dark and sometimes return intact.

Eimear McBride

The Tale of Kathleen

Hag

by Daisy Johnson

by Kirsty Logan

by Emma Glass

by Eimear McBride

by Natasha Carthew

by Mahsuda Snaith

by Naomi Booth

by Liv Little

by Imogen Hermes Gowar

by Irenosen Okojie

'Engaging, modern fables with a feminist tang' Sunday Times

DARK, POTENT AND UNCANNY, HAG BURSTS WITH THE UNTOLD STORIES OF OUR ISLES, CAPTURED IN VOICES AS VARIED AS THEY ARE VIVID.

Here are sisters fighting for the love of the same woman, a pregnant archaeologist unearthing impossible bones and lost children following you home. A panther runs through the forests of England and pixies prey upon violent men.

From the islands of Scotland to the coast of Cornwall, the mountains of Galway to the depths of the Fens, these forgotten folktales howl, cackle and sing their way into the 21st century, wildly reimagined by some of the most exciting women writing in Britain and Ireland today.

'A thoroughly original package that has a hint of Angela Carter' The Times

'Sharp writing and cleverly done' Spectator