Read an extract from Jack by Marilynne Robinson

Return to Gilead one more time.

Return to Gilead one more time.

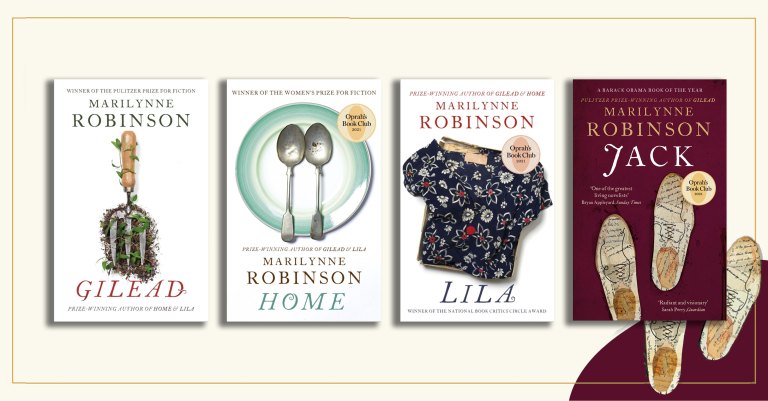

In this fourth and final novel in Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead series we learn more about Jack Boughton – the loved and grieved-over prodigal son.

Set before Gilead, Home and Lila, just after World War II, the grieved over prodigal son, a drunkard and a ne’er-do-well, has left home for St. Louis. In that segregated city Jack falls in love with African American high school teacher, Della Miles. A preacher’s daughter, Della is a woman with a discriminating mind, a generous spirit and an independent will. This is their fraught and beautiful love story.

‘[Her work] defines universal truths about what it means to be human’ Barack Obama

‘Marilynne Robinson is one of the greatest writers of our time’ Sunday Times

‘Jack is the fourth in Robinson’s luminous, profound Gilead series and perhaps the best yet’ Observer

READ THE FIRST CHAPTER HERE:

He was walking along almost beside her, two steps behind. She did not look back. She said, “I’m not talking to you.”

“I completely understand.”

“If you did completely understand, you wouldn’t be following me.”

He said, “When a fellow takes a girl out to dinner, he has to see her home.”

“No, he doesn’t have to. Not if she tells him to go away and leave her alone.”

“I can’t help the way I was brought up,” he said. But he crossed the street and walked along beside her, across the street. When they were a block from where she lived, he came across the street again. He said, “I do want to apologize.”

“I don’t want to hear it. And don’t bother trying to explain.”

“Thank you. I mean I’d rather not try to explain. If that’s all right.”

“Nothing is all right. All right has no place in this conversation.” Still, her voice was soft.

“I understand, of course. But I can’t quite resign myself.”

She said, “I have never been so embarrassed. Never in my life.”

He said, “Well, you haven’t known me very long.”

She stopped. “Now it’s a joke. It’s funny.”

He said, “There’s a problem I have. The wrong things make me laugh. I think I spoke to you about that.”

“And where did you come from, anyway? I was just walking along, and there you were behind me.”

“Yes. I’m sorry if I frightened you.”

“No, you didn’t. I knew it was you. No thief could be that sneaky. You must have been hiding behind a tree. Something ridiculous.”

“Well,” he said, “in any case, I have seen you safely to your door.” He took out his wallet and extracted a five- dollar bill.

“Now, what is this! Giving me money here on my doorstep? What are people supposed to think about that? You want to ruin my life!”

He put the money and the wallet back. “Very thoughtless of me. I just wanted you to know I wasn’t ducking out on the check. I know that’s what you must think. You see, I did have the money. That was my point.”

She shook her head. “Me scraping around in the bottom of my handbag trying to put together enough quarters and dimes to pay for those pork chops we didn’t eat. I left owing the man twenty cents.”

“Well, I’ll get the money to you. Discreetly. In a book or something. I have those books of yours.” He said, “I thought it was a very nice evening, till the last part. One bad hour out of three. One small personal loan, promptly repaid. Maybe tomorrow.”

She said, “I think you expect me to keep putting up with you!”

“Not really. People don’t, generally. I won’t blame you. I know how it is.” He said, “Your voice is soft even when you’re angry. That’s unusual.”

“I guess I wasn’t brought up to quarrel in the street.”

“I actually meant another kind of soft.” He said, “I have a few minutes. If you want to talk this over in private.”

“Did you just invite yourself in? Well, there’s nothing to talk over. You go home, or wherever it is you go. I’m done with this, what ever it is. You’re just trouble.”

He nodded. “I’ve never denied it. Seldom denied it, anyway.”

“I’ll grant you that.”

They stood there a full minute.

He said, “I’ve been looking forward to this evening. I don’t quite want it to end.”

“Mad as I am at you.”

He nodded. “That’s why I can’t quite walk away. I won’t see you again. But you’re here now—”

She said, “I just would not have believed you would embarrass me like that. I still can’t believe it.”

“Really, it seemed like the best thing, at the time.”

“I thought you were a gentleman. More or less, anyway.”

“Very often I am. In most circumstances. Dyed-in-the-wool, much of the time.”

“Well, here’s my door. You can leave now.”

“That’s true. I will. I’m just finding it a little difficult. Give me a couple of minutes. When you go inside, I’ll probably leave.”

“If some white people come along, you’ll be gone soon enough.”

He took a step back. “What? Do you think that’s what happened?” “I saw them, Jack. Those men. I’m not blind. And I’m not stupid.”

He said, “I don’t know why you are even talking to me.”

“That’s what I’d like to know, myself.”

“They were just trying to collect some debts. They can be pretty rough about it. I can’t risk, you know, an altercation. The last one almost got me thirty days. So that would have embarrassed you, maybe more.”

“You are something!”

“Maybe,” he said, “but I’m not— I’m so glad you told me. I could have left you here thinking— I wouldn’t want you to—”

“The truth isn’t so much better, you know. Really—”

“Yes, it is. Sure it is.”

“So now I’m supposed to forgive you because what you did isn’t the absolutely worst thing you could have done.”

“Well, the case could be made, couldn’t it? I mean, I feel much better now that we’ve cleared that up. If I’d walked away ten minutes ago, think how different it would have been. And then I really never would have seen you again.”

“Who said you will now?”

He nodded. “I can’t help thinking the odds are better.”

“Maybe, if I decide to believe you. Maybe not.”

“You really ought to believe me,” he said. “What harm would it do? You can still hang up on me if I call. Return my letters. Nothing would be different. Except you wouldn’t have to have such unpleasant thoughts about how you’ve spent a few hours over a couple of weeks. That splendid evening we meant to have. You could forgive me that much.”

“Forgive myself,” she said. “For being so foolish.”

“You could think of it that way, too.”

She turned and looked at him. “ Don’t laugh at this, any of this, ever,” she said. “I think you want to. And if you’re trying to be ingratiating, it isn’t working.”

“It doesn’t work. How well I know. It is some spontaneous, chemical thing that happens. Contact between Jack Boughton and— air. Like phosphorus, you know. No actual flame, of course. Foxfire, more like that. A rosy heat of embarrassment around any ordinary thing. No way to hide it. I suppose entropy should have a nimbus—”

“Stop talking,” she said.

“It’s nerves.”

“I know it is.”

“Pay no attention.”

“You’re breaking my heart.”

He laughed. “I’m just talking to keep you here listening. I certainly don’t mean to break your heart.” “No, you’re telling me the truth now. It’s a pity. I have never heard of a white man who got so little good out of being a white man.”

“It has its uses, even for me. I am assumed to know how many bubbles t here are in a bar of soap. I’ve had the honor of helping to make civic dignitaries of some very unlikely chaps. I’ve—”

“Don’t,” she said. “Don’t, don’t. I have to talk about the Declaration of Independence on Monday. There is nothing funny about that.”

“True. Not a thing.” He said, “I really am going to say some-thing true, Miss Della. So listen. This doesn’t happen every day.” Then he said, “It’s ridiculous that a preacher’s daughter, a high-school teacher, a young woman with excellent prospects in life, would be hanging around with a confirmed, inveterate bum. So I won’t bother you anymore. You won’t be seeing me again.” He took a step away.

She looked at him. “You’re telling me goodbye! Why do you get to do that? I told you goodbye and you’ve kept me here listening to your nonsense so long I’d almost forgotten I said it.”

“Sorry,” he said. “I see your point. But I was trying to do what a gentleman would do. If a gentleman could actually be in my situation here. I could cost you everything, and there’s no good I could ever do you. Well, that’s obvious. I’m saying goodbye so you’ll know I understand how things are. I’m actually making you a promise, and I’ll stick to it. You’ll be impressed.”

She said, “Those books you borrowed.”

“They’ll be on your porch step tomorrow. Or soon after. With that money I owe you.”

“I don’t want them back. No, maybe I do. I suppose you wrote in them.”

“Pencil only. I’ll erase it.”

“No, don’t do that. I’ll do it.”

“Yes, I can see that there might be satisfactions involved.”

“Well,” she said, “I told you goodbye. You told me goodbye. Now walk away.”

“And you go inside.”

“As soon as you’re gone.”

They laughed.

After a minute, he said, “You just watch. I can do this.” And he lifted his hat to her and strolled off with his hands in his pockets. If he did look back, it was after she had closed the door behind her.