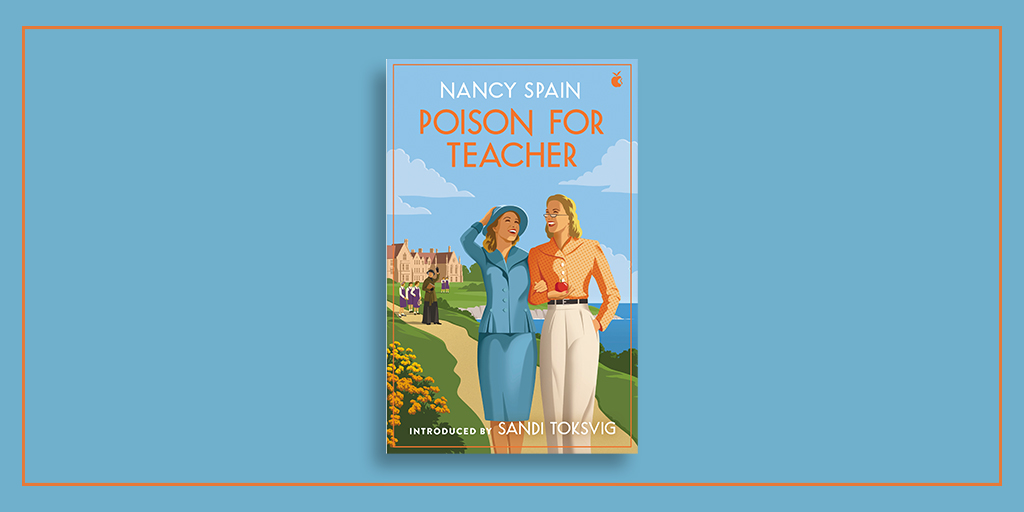

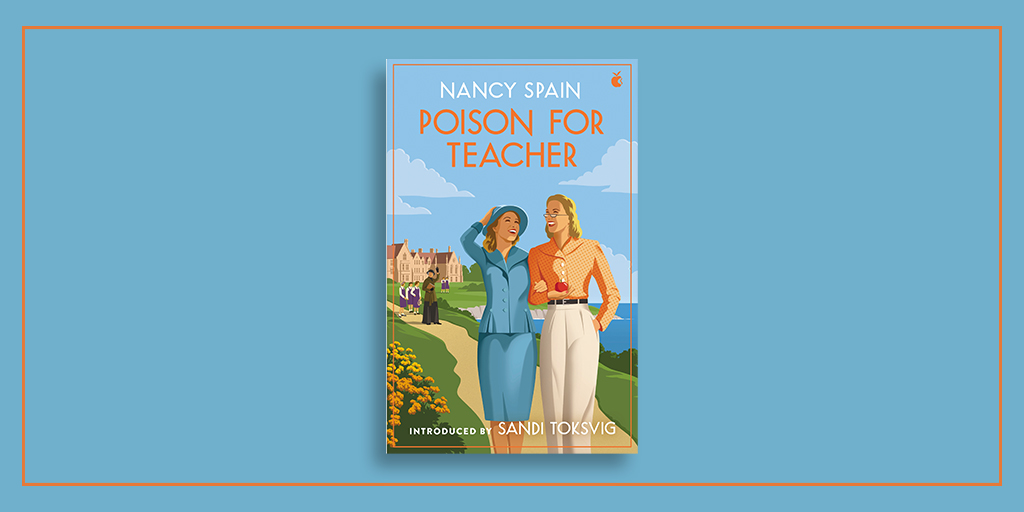

Sandi Toksvig on Poison for Teacher

INTRODUCTION

‘The world of books: romantic, idle, shiftless world so beautiful, so cheap compared with living’ – NANCY SPAIN

I never met Nancy Spain, and I’ve been worrying that we might not have got on. It bothers me because I’m a fan. That’s probably an odd start for someone writing an introduction to her work, but I think it’s a sign of how much I like her writing that I ponder whether we would have clicked in person. The thing is, Spain loved celebrity. In 1955 she wrote, ‘I love a big name . . . I like to go where they go . . . I always hope (don’t you?) that some of their lustre will rub off against me . . . ’

I don’t hope that. I loathe celebrity and run from gatherings of the famous, so I can’t say I would have wanted to hang out with her, but I should have liked to have met. I would have told her what a brilliant writer she was, how hilarious, and I’d have said thank you, because I also know that I might not have had my career without her. I’ve been lucky enough to earn a crust by both writing and broadcasting, and I do so because Nancy Spain was there first.

During the height of her fame in the 1950s and early 60s she did something remarkable – she became a multimedia celebrity at a time when no one even knew that was a desirable thing. She was a TV and radio personality, a novelist, a journalist and columnist for British tabloids. She did all this while wearing what

was known as ‘mannish clothing’. Although her lesbianism was not openly discussed, she became a role model for many, with the closeted dyke feeling better just knowing Spain was in the public eye being clever and funny.

I am too young to have seen her on TV, but the strange thing about the internet is that people never really disappear. Check Nancy Spain out on the web and you can still see and hear her performing in a 1960s BBC broadcast on the panel of Juke Box Jury. She has the clipped tones of a well-bred Englishwoman of the time, who sounds as though she is fitting in a broadcast before dashing to the Ritz for tea. It is a carefully contrived public persona that suited Spain as a way to present herself to the world but, like so much of her life, it skirted around the truth. She was selling the world a product, a concept which she would have understood only too well.

In 1948 Spain wrote a biography of her great-aunt, Isabella Beeton, author of the famous Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management. Although it was an encyclopedic presentation of all you needed to know about running the home, Isabella Beeton was hardly the bossy matron in the kitchen that the book suggested; in fact she wrote it aged just twenty- one, when she can hardly have had the necessary experience. Isabella probably knew more about horses, having been a racing correspondent for Sporting Life. The truth is that she and her husband Sam saw a gap in the book market. So, rather than being the distillation of years of experience, Mrs Beeton’s book was a shrewd marketing ploy. I wonder how many people know that Isabella never did become that wise old woman of the household because she died aged just twenty- eight of puerperal fever following the birth of her fourth child? There are parallels here too, for Spain’s background was also not what it seemed and she, like Isabella, lost her life too early.

Far from being a posh Londoner, Nancy Spain hailed from Newcastle. Her father was a writer and occasional broadcaster, and she followed in his footsteps quite aware that she was the son he never had. Her determination to come to the fore appeared early on. As a child she liked to play St George and the Dragon in which her father took the part of the dragon, Nancy marched about as St George while, as she described it, her sister Liz ‘was lashed to the bottom of the stairs with skipping ropes and scarves’. No dragon was going to stop Spain from being the hero of the piece.

From 1931 to 1935 Spain was sent, like her mother before her, to finish her education at the famous girls’ public school Roedean, high on the chalky cliffs near Brighton. It was here that her Geordie accent was subdued and polished into something else. She didn’t like it there and would spend time getting her own back in her later writing. Her fellow classmates seem to have varied in their attitude towards her. Some saw her as exotic and clever, while others found her over the top. It says something about the attitude to women’s careers at the time when you learn that in his 1933 Prize- Giving Day speech to the school the then Lord Chancellor, Lord Sankey, congratulated Roedean on playing ‘a remarkable part in the great movement for the higher education of women’, but added, ‘In spite of the many attractive avenues which were now open to girls’, he hoped ‘the majority of them would not desert the path of simple duties and home life’.

Deserting that path was Spain’s destiny from the beginning. It was while at school that Spain began writing a diary of her private thoughts. In this early writing the conflict between her inner lesbian feelings and society’s demand that she keep them quiet first stirred. She began to express herself in poetry. Some of her verse- making was public and she won a Guinea prize for one of her works in her final year. This, she said, led her to the foolish notion that poems could make money.

Her mother harboured ambitions for Spain to become a games or domestic science teacher, but it was clear neither was going to happen. Her father, who sounds a jolly sort, said she could stay home and have fifty pounds a year to spend as she pleased. She joined a women’s lacrosse and hockey club in Sunderland because it looked like fun, but instead she found a fledgling career and her first love. She became utterly smitten with a fellow team member, twenty- three- year- old Winifred Emily Sargeant (‘Bin’ to her friends) a blonde, blue- eyed woman who could run fast on the field and rather glamorously seemed fast off it by drinking gin and tonic.

The Newcastle Journal decided to publish some reports about women’s sport and almost by chance Nancy got her first job in journalism. Touring with the team meant she could both write and spend time with Bin. When she discovered her feelings for Winifred were reciprocated, she was over the moon.

Dearest – your laughter stirred my heart

for everything I loved was there –

Oh set its gaiety apart

that I may feel it everywhere!

She bought herself a second-hand car for twenty pounds and began making some local radio broadcasts, getting her first taste of fame when she played the part of Northumberland heroine Grace Darling in a local radio play. Meanwhile she and Winifred found time to escape. It was the 1930s and they were both supposed to be growing into ‘respectable’ women. The pressure must have been unbearable as there was no one with whom they could share the excitement of their feelings for each other. They went off for several weeks to France on a touring holiday, which Spain described as idyllic. It was to be a one-off, for they returned to find Britain declaring war with Germany. They both joined up, with Spain enlisting in the Women’s Royal Naval Service, the Wrens.

She would later describe her time in the service as the place where she found emancipation. She became a driver, scooting across the base and fixing the vehicles when they faltered. Based in North Shields, where many large naval vessels came in for repairs, it was often cold and there was no money for uniforms. Some trawlermen gave her a fisherman’s jersey, and she got a white balaclava helmet that she was told was made by Princess Mary. She also got permission to wear jodhpurs on duty. It was the beginning of her feeling comfortable in men’s clothes.

At the end of 1939 news reached Spain that Winifred, aged twenty- seven, had died of a viral infection. Unable to bear the grief, she didn’t go to the funeral, but instead wrote poetry about the efficacy of drink to drown sorrows. The Wrens decided she was officer material and moved her to Arbroath in Scotland to do administrative duties. It was here that she began to shape the rest of her life. She became central to the base’s many entertainments. She took part in broadcasts. She wrote. She was always busy. She did not talk about her life with Winifred. Years later, when she wrote about their dreamy French holiday, she wrote as if she had gone alone. Her only travelling companions apparently were ‘a huge hunk of French bread and a slopping bottle of warm wine’. The descriptions of the trip are splendid, but they mask the painful truth.

After the war, Spain was set to be a writer. An outstanding review by A. A. Milne of her first book, Thank you – Nelson, about her experiences in the Wrens, gave her a first push to success. She sought out the famous, she lived as ‘out’ as she could in an unaccepting world. I don’t like how the tabloids sold her to the public. The Daily Express declared about its journalist, as if it were a selling point: ‘They call her vulgar . . . they call her unscrupulous . . . they call her the worst dressed woman in Britain . . . ’

She called herself a ‘trouser-wearing character’, with her very clothing choices setting her apart as odd or bohemian. I suspect she was just trying to find a way to be both acceptable to the general public, and to be herself. It is a tricky combination, and was much harder then. She may not have known or intended the impact she had in helping to secretly signal to other lesbians and gay men that they were not alone. She lived with the founder and editor of She magazine, Joan ‘Jonny’ Werner Laurie, and is said to

have slept with many other women, including Marlene Dietrich. Fame indeed.

I am so thrilled to see her work come back into print. Her detective novels are hilarious. They are high camp and less about detecting than delighting, with absurd farce and a wonderful turn of phrase. Who doesn’t want to read about a sleuth who when heading out to do some detective work hangs a notice on her front door reading ‘OUT – GONE TO CRIME’? Her detective, Miriam Birdseye, was based on Spain’s friend the actress Hermione Gingold whose own eccentricities made her seem like a character from a novel. Miriam’s glorious theatricality is complemented by her indolent sidekick, the (allegedly) Russian ballerina Natasha Nevkorina, who has to overcome a natural disinclination to do anything in order to do most of the actual detecting. They work incredibly well together as in this exchange:

‘And she is telling you that you are going mad, I suppose?’ said Natasha.

‘Yes,’ said Miss Lipscoomb, and sank into a chair. She put her head in her hands. ‘I think it is true,’ she said. ‘But how did you know?’

‘That’s an old one,’ said Miriam briskly. ‘I always used to tell my first husband he was going mad,’ she said. ‘In the end he did,’ she added triumphantly.

There is something quintessentially British about these detective novels, as if every girl graduating from Roedean might end up solving a murder. The books contain jokes that work on two levels – some for everyone; some just for those in the know. Giving a fictitious school the name Radcliff Hall is a good queer gag, while anyone might enjoy the names of the ‘intimate revues’ in which Miriam Birdseye had appeared in the past, including ‘Absolutely the End’, ‘Positively the Last’ and ‘Take Me Off’.

Seen through the prism of modern thinking, there are aspects of Spain’s writing that are uncomfortable, but I am sad if they overshadow her work so thoroughly as to condemn it to obscurity. P. G. Wodehouse has, after all, survived far worse accusations. Thomas Hardy is still recalled for his writing about ‘man’s inhumanity to man’, even though by all accounts he wasn’t nice to his wife. Should we stop reading Virginia Woolf because she was a self-confessed snob? I am not a big fan of the modern ‘cancel culture’, and hope we can be all grown- up enough to read things in the context of their time. Of one thing I am certain – Spain was not trying to hurt anyone. She had had too tough a time of her own trying to be allowed just to survive the endless difficulties of being other. My political consciousness is as raised as anyone’s, and I see the flaws, but maybe it’s okay just to relax in her company and succumb to being entertained.

Nancy Spain died aged forty- seven. She was in a light aircraft on her way to cover the 1964 Grand National when the plane crashed near the racecourse. Her partner Jonny was with her and they were cremated together. Her friend Nöel Coward wrote, ‘It is cruel that all that gaiety, intelligence and vitality should be snuffed out, when so many bores and horrors are left living.’ She was bold, she was brave, she was funny, she was feisty. I owe her a great deal in leading the way and I like her books a lot. They make me laugh, but also here I get to meet her alone, away from the public gaze, and just soak up the chat. Enjoy.

Sandi Toksvig

'Her detective novels are hilarious - less about detecting than delighting, with absurd farce and a wonderful turn of phrase . . . Nancy Spain was bold, she was brave, she was funny, she was feisty' SANDI TOKSVIG

Miriam Birdseye, ex-revue star and now professional sleuth, is intrigued when the headmistress of Radcliff Hall arrives at her Baker Street detective agency. A series of bizarre stunts that at first seemed like pranks have taken a sinister turn, and since Mis Lipscoomb found her gym rope half sawn through, she's begun to fear not only for her school, but for her life.

This is how Miriam and her friend, Russian ballerina Natasha Nevkorina, find themselves on board the train to a Sussex girls' school, in the unlikely guise of teachers. Before long the detective duo uncovers a blackmail plot, infidelity and a dizzying array of school schisms. And then a teacher is poisoned during the school play; can they discover the culprit before the body count rises?

From the pen of Nancy Spain, for whom farce and humour are a lot more fun than a conventional detective novel, the result is a deliciously wild ride.

'An either intense or sombre approach to crime is to Miss Spain foreign: in her world an inspired craziness rules . . . Her wit, her zest, her outrageousness, and the colloquial stylishness of her writing are quite her own'

Elizabeth Bowen