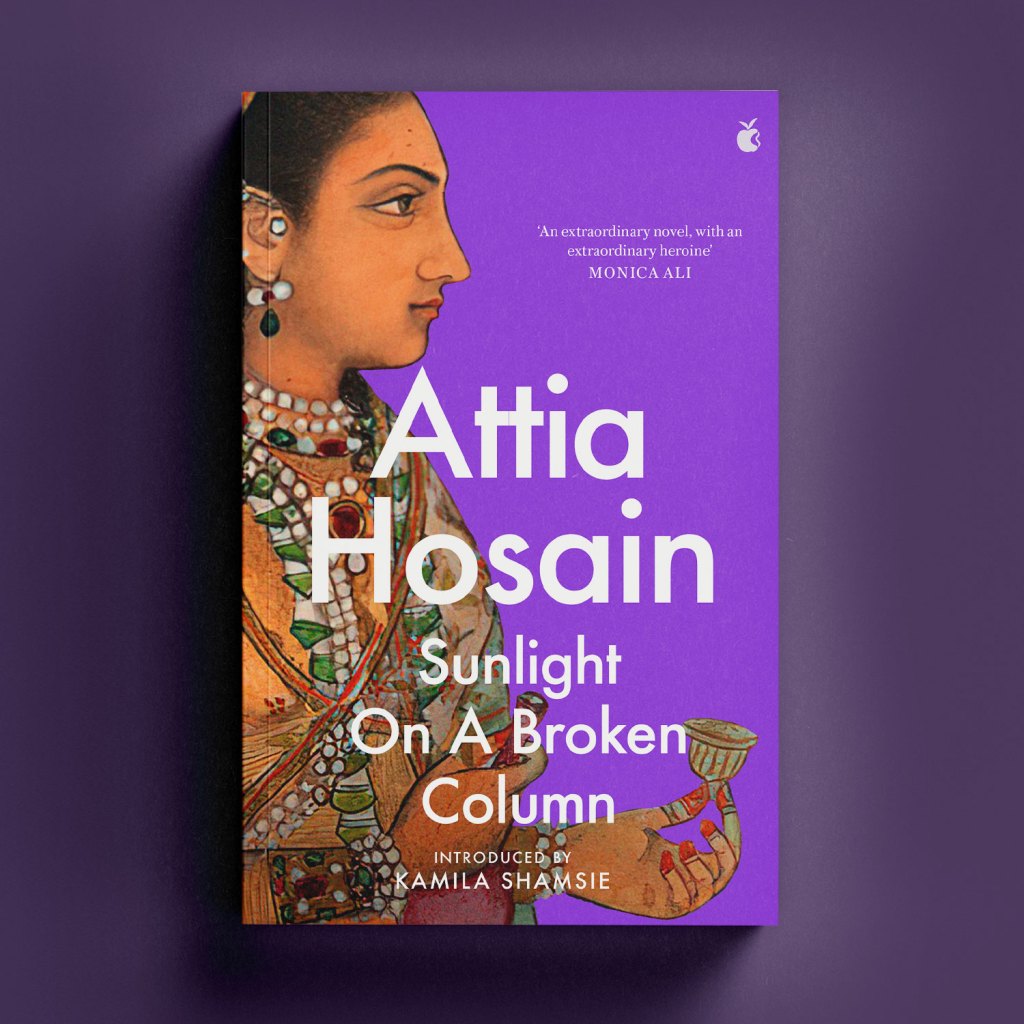

Read an extract from Sunlight on a Broken Column by Attia Hosain

First published sixty years ago, Sunlight on a Broken Column is an unforgettable coming-of-age story set against the tumultuous background of Partition.

Laila, orphaned daughter of a distinguished Muslim family, is brought up in her grandfather’s traditional household by her aunts, who keep purdah. At fifteen she moves to the home of her ‘liberal’ but autocratic uncle in Lucknow. As the struggle for Independence sharpens, Laila is surrounded by relatives and university friends caught up in politics, but she is unable to commit herself to any cause: her own fight for independence is a struggle against tradition.

With its stunning evocation of India, its political insight and unsentimental understanding of the human heart, Sunlight on a Broken Column is a classic of Muslim life.

Features an introduction by Kamila Shamsie.

Read an extract:

CHAPTER ONE

The day my aunt Abida moved from the zenana into the guest- room off the corridor that led to the men’s wing of the house, within call of her father’s room, we knew Baba Jan had not much longer to live.

Baba Jan, my grandfather, had been ill for three months and the sick air, seeping and spreading through the straggling house, weighed each day more oppressively on those who lived in it.

Aunt Abida withdrew into a tight cocoon of anxious silence, while Aunt Majida dissolved into tearful prayers. The quarrels of the maid- servants were desultory and less shrill; the men- servants’ voices did not now carry over the high wall; the sweeper, the gardeners and the washerman drank less and sang no more to the rhythm of the drum. Visitors spoke as if some-one was asleep next door, and Zahra and I felt our girlhood a heavy burden. Our minds had no defences against anxiety; we were uncertain and afraid.

I began reading even more than I normally did, with no censor to guard Baba Jan’s library now, until Hakiman Bua, who had fed and nursed me, changed from her admiring, ‘My little bookworm finds no time for mischief’ to remonstrating, ‘Your books will eat you. They will dim the light of your lovely eyes, my moon princess, and then who will marry you, owl-eyed, peering through glasses? Why are you not like Zahra, your father’s – God rest his soul – own sister’s child, yet so different from you? Pull your head out of your books and look at the world, my child. Read the Holy Book, remember Allah and his Prophet, then women will fight to choose you for their sons.’

Zahra said her prayers five times a day, read the Quran for an hour every morning, sewed and knitted and wrote the accounts; but now all these things which she had always done merely interrupted her aimless wandering through the corridors and courtyards, returning always to sit by me though we had nothing in common but our kinship and our fears. Her attempts at conversation wheeled round a constant pivot.

‘What do you think will happen after he dies?’

‘I don’t know.’

And then variations on a theme.

‘Do you think Hamid Mamoon will retire and come to live here?’

‘How should I know?’

‘Do you think he will let us live here?’

‘Why not?’

‘He has such English ideas.’

‘Don’t be silly.’

‘Do you think you’ll go to College?’

‘Why not?’

‘How do you know what will happen after Baba Jan dies?’

‘Do you? Does anyone?’

CHAPTER TWO

It was my fifteenth birthday. Not that it mattered to anyone else. My birthday was remembered only by me, and while at school, by the teachers when forms had to be filled up. Or by Sita, the only companion of my choice, whom I missed today because she had gone away on a holiday, and whom I envied always because she had a father, a mother, a brother . . .

At home if I mentioned it, my aunt Abida, who had brought me up, would say, ‘Your birthday? How old are you? Really? How quickly the years pass! Why, you are no longer a child.’ And Hakiman Bua would say, ‘Now let me see, light of my eyes, when were you born? The year you fell, Abida Bitia, and broke your arm; the year of the floods when the rivers came up to the fields across the road, and Ahmed Mian, her father, God rest his soul, went to the courts by boat, and was happy not knowing the future. Yes it was the year of the floods.’

Fifteen; and the years were endless corridors stretching before and after. Fifteen; and how thin and shapeless, and not yet taller than last year’s mark on the tall mirror’s frame . . .

Inside the glass the light shivered, and the door opened. I turned quickly in embarrassment towards Zahra, but she had not noticed me looking at myself. She was too full of some personal excitement which shone in her eyes and quickened her movements. Her eyes were large, slanting and protruded slightly, and she emphasised them with the line of kajal drawn outwards, dark and long at the corners. She used them to ask favours and to attract sympathy. They drew attention away from her commonplace nose, her greedy mouth. I thought they squinted inwards slightly, and no wonder because she saw everything through herself.

‘Ammi sent for Baba Mian this morning, and he is with them now, and Mohsin Mamoon too,’ she said with nasal tones of excitement in her voice.

‘What is peculiar about that? Mohsin Chacha is always wandering in and out; and if Baba Mian was sent for, is that strange considering he is so busy saving his soul he forgets his brother is dying?’

‘God forbid!’ said Zahra automatically, then added in her earlier tone, ‘It is about me they want to talk. And they will be sending for us soon.’

‘How do you know?’

‘I was just going in to ask Ammi something,’ she said slyly, sharing a pleasant secret, ‘when I heard what they were saying. Then I heard Ammi ask Hakiman Bua to call us and I ran away. Hakiman Bua is so slow.’ She giggled.

Zahra found amusing ugliness in that dark bulk which to me embodied the abundance of comforting love.

‘Laila Bitia! Zahra Bitia!’ Hakiman Bua’s voice came high and urgent from the corridor.

‘There, you see,’ whispered Zahra as she sat down on her bed. ‘Now, remember, I have been with you a long time.’ Then she called out, ‘What is it, Hakiman Bua? We’re here.’

Hakiman Bua came in slowly, heavily, grumbling, ‘The miles one has to walk in this house! My legs are weighted with lead, and every joint has needles stuck into it.’ And without pausing she changed to her tender scolding, ‘Child, put away that book. Those insect letters will eat away your eyes. Now then, hurry! Abida Bitia is calling both of you.’

‘Bua, Bua,’ I said, hugging her. ‘These books will be garlands of gold round my neck.’

I followed Zahra out of the room but walked slowly, not wishing to leave Hakiman Bua too far behind. She shuffled along, holding up her wide, trailing pyjamas. Her heavy, silver anklets looked incongruous worn over my discarded black school stockings.

When we came to the drawing-room that united the two wings of the house, I drew nearer to Zahra. Into this vast room the coloured panes of the arched doors let in not light but shadows that moved in the mirrors on the walls and mantel-piece, that slithered under chairs, tables and divans, hid behind marble statues, lurked in giant porcelain vases, and nestled in the carpets. Footsteps sounded sharp on the marble floor and chased whispered echoes from the high, gilded roof. In this, the oldest portion of the house, I heard notes of strange music not distinctly separate but diffused in the silence of some quiet night as perfume in the air. I heard too the jingling of anklet bells.

But no one knew any of this.

In the corridor beyond there was light. It broke into the pat-terns of the fretted stone that screened this last link between the walled zenana, self- contained with its lawns, courtyards and veranda’d rooms, and the outer portion of the house.

Through the curtained door of the guest-room came the sound of voices in argument; the old, tremulous voice of Baba Mian, my great uncle Musa, crushed by the swaggering voice of Uncle Mohsin, whose degree of relationship, much to his annoyance, I found it hard to remember. He was the son of my grandfather’s father’s sister’s daughter. He used to taunt me that if I could not remember such close relationships I would surely achieve my nirvana and become so English that my aunts and cousins would be strangers to me.

Silence fell as we came in, and as I lifted my hand to say ‘Adab’ in salutation I moved out of reach of Uncle Mohsin’s outstretched arm, and went over to Baba Mian, who kissed me lightly on the brow, saying, ‘Live long in the protection of Allah, my child.’

Then he leaned back against the huge, white bolster, his restless fingers counting the amber beads of his tasbih, his eyes closed. Even when he spoke he kept them closed for the most part, and he swayed gently as he talked, his brow perplexed. Sometimes, even when no sound came, his lips moved in the crumpled face, framed by the white hair cropped round his ears, and by the gently straggling beard that flowed in thin wisps towards his chest. He wore a thick, quilted, black cotton waistcoat over his warm grey shirt, and his tight flannel pyjamas were crumpled at the knees, through sitting with bent knees in long hours of prayer.

I went and sat near Aunt Abida on her bed. She sat with one knee drawn up to her chin, her hands crossed over it so that the knuckles were white. The shadows of her pale yellow dopatta accentuated the pallor of her drawn face. Her eyes were wide and restless.

Zahra responded to Uncle Mohsin’s invitation. He drew her near, rubbed his chin on her cheek and she squealed, ‘You haven’t shaved properly.’

He had a laugh that coiled out of fat-globuled honeyed depths, and bold eyes, red flecked. He sat on a chair facing the others, his legs stretched out and crossed, their strong muscles moulded by the fine white cotton pyjamas, tightly drawn over the calves, loosely gathered at the ankles, finely hand-stitched at the seams. He had a habit of rapidly shaking one foot as he spoke, almost slipping off the black velvet, gold-stitched shoe.

Aunt Majida, a large, loose bundle wrapped in a grey shawl, was cutting betel nuts nervously, her nose a little red, her eyes washed with recent tears. She had a calm, broad forehead, but her mouth was frightened and tremulous, and her cheeks sagged with depressing, downward lines.

Zahra sat by her mother and played with one of the carved, wooden cones placed at each corner of the takht to weight the white sheet stretched across it.

‘And now that your absurd wish is granted, Abida,’ said Uncle Moshin, ‘now that the girls are here, have we your per-mission to continue our conversation?’ His voice had echoes like the reflection of a complacent man smiling at himself in a mirror.

‘In the presence of my elders,’ Aunt Abida replied coldly, ‘I am not the one to be asked for permission; but your definition of absurdity, and mine, might permit of a great degree of difference, Mohsin Bhai.’

‘No doubt, no doubt. How can I understand the workings of the mind of a scholar of Persian poetry and Arabic theology infected with modern ideas?’ said Uncle Mohsin with heavy sarcasm; and I heard Aunt Abida draw in a sharp breath.

Though Uncle Mohsin was the most frequent visitor amongst the male relatives allowed into the zenana, I noticed with acid pleasure how casually Aunt Abida treated him when she was not actually inimical. Zahra, characteristically, had discovered that he had wanted to marry Aunt Abida when young.

‘Mohsin Bhai,’ pleaded Aunt Majida, ‘nothing will be gained by losing your temper. My poor head aches, so that to think is an added pain.’

Aunt Majida’s head ached perpetually and thinking was never without pain.

‘Ya Allah! Ya Rahman! Ya Rahim!’ breathed Baba Mian, and with eyes still closed said gently, ‘I have seen many things in my long life, and who knows the definition of anything but the Almighty? He draws us into error to prostrate our pride, and from error to savour His salvation. Only Death is a certainty.’

There was a moment of cold silence in the room. Baba Mian was so old; death must have tired of his companionship and moved over to Baba Jan whose forceful old age was a challenge.

I looked at Zahra to share my bewilderment but she was looking demurely down, calm with secret knowledge.

Uncle Mohsin twirled the fine points of his moustaches, and prodded the carpet with his silver-topped stick.

‘I consider all those things absurd that are purposeless,’ he said, just as if Baba Mian had not spoken. ‘Is the girl to pass judgement on her elders? Doubt their capability to choose? Question their decision? Choose her own husband?’

Aunt Abida’s pale lips trembled as she spoke. ‘No, Mohsin Bhai, none of these things, I have neither the power, nor the wish, because I am not of these times. But I am living in them. The walls of this house are high enough, but they do not enclose a cemetery. The girl cannot choose her own husband, she has neither the upbringing nor the opportunity—’

‘Would you have it otherwise?’ he interrupted.

‘But,’ she ignored him, ‘she can be present while we make the choice, hear our arguments, know our reasons, so that later on she will not doubt our capabilities and question our decisions. That is the least I can do,’ she added bitterly.

‘We would not be scheming behind her back if she were not here. Our elders did not think our presence necessary, and we believed in their wisdom. It was a good enough system for them and for us,’ he said angrily.

‘Was it?’ Aunt Abida’s anger matched his own.

Uncle Mohsin’s eyes flamed and flickered.

In that moment of hesitation was concentrated the smudged failure of his life. Even we, the young ones, knew stories about him and the dancing girls of the city. The eldest of his four children was our age, sullenly obedient to a father she seldom saw and hated for her mother’s sake. The mother, a negative, ailing woman, her tattered beauty a mendicant for love, knew her husband only to conceive a child after each infrequent visit home. He lived in the city with friends or relations, had a wide and influential circle of friends, dressed well, composed poetry, was an authority on classical music and dancing, and never did any work.

I disliked him.

His eyes searched for reactions, but Baba Mian was telling his beads and Aunt Majida was cutting betel nut and sniffing.

‘Look, Abida,’ he said aggressively, but with less self-assertion, ‘I have not come here to argue with you. I came here with a proposal which you can refuse or accept; but I want an answer either way, and soon. Baba Jan’s condition is well known to all of you. We have to make plans for the future of these girls, keeping in mind what is to happen to them, God forbid, after his death.’

‘What will happen to them? What will happen to us?’ wailed Aunt Majida. ‘Look at me, a widow, and this child of mine, a girl without a father. Where will we go? And Abida, look at her, still unmarried! Abba found no one good enough for her; and refused one good proposal after another. And now what is to become of her when he leaves her so cruelly alone? What is to become of us?’ she sobbed, and Zahra clung to her, also crying.

Aunt Abida’s hands were trembling as she drew her dopatta over her head and turned towards her sister. ‘Do not raise your voice,’ she said wearily, ‘Abba is asleep.’

I felt cold deep down inside me.

Aunt Majida wiped her eyes and nose with a corner of her shawl and moaned, ‘Oh what a miserable, ill-fated woman am I!’

‘Ya, Rahman, Ya, Rahim!’ said Baba Mian softly.

Uncle Mohsin cleared his throat impatiently, twisted his silver-knobbed stick, and said, ‘You must think now of the future. Zahra is seventeen and ready for marriage. I have brought you a proposal and you must come to some kind of decision. Whom else would you like to consult? Your father is ill. Your brother is not here, Baba Mian and I—’

‘Hamid Mian will be coming home very soon,’ Aunt Majida interrupted.

‘Will that make any difference? He is more a sahib than the English. He will not take the responsibility.’

‘But he must be consulted; it is not right that he should not be,’ she said obstinately.

‘Of course he will be, so as not to hurt his precious pride. But the decision can be made first. It is not easy to find suitable young men, and if you let this chance slip, how long will you have Zahra on your hands with your own future uncertain?’

Her sister’s moans were cut short by Aunt Abida’s sharp retort:

‘You talk as if we were choosing a new horse for the carriage.’

‘Horses, my dear Abida, are chosen with more care than husbands these days. It is fashionable to decry the pedigree of men and to pay fortunes for the pedigrees of horses and dogs. Soon you will have to apologise for your birth and breeding, and not be proud of them. And now let me have an answer one way or another. Though you have insisted on staging this discussion as a ridiculous scene, with the girls as an audience, I am sure Zahra will do as her elders decide. She has not had the benefit of a memsahib’s education; though I am glad to see certain abhorrent signs of it have been removed, and your young memsahib has given up walking around dressed like a native Christian.’

The cold stone inside me was now burning lead. Aunt Abida put her hand on mine, and her voice was sharp like slivers of ice. ‘What Laila wears or does is not under discussion.’

Aunt Majida said reproachfully, ‘Mohsin Bhai, Laila was educated as her father would have wished. Abida carried out a beloved brother’s wishes as not even the child’s own mother could have done had she been spared to see her grow up. Even Abba respected his son’s beliefs and set aside his own, so, God knows, you have no right to criticise.’

Uncle Mohsin blustered, ‘I have every right to say what I believe is correct. I do not talk behind people’s backs. That is my trouble, I am too honest. I say what I do because of my love and concern for the family. I do not want my nieces put in the way of temptation. After all, Zahra was brought up differently, correctly, sensibly.’

Aunt Abida’s voice cracked with anger, ‘I have told you I am not prepared to discuss this matter with you, Mohsin Bhai.’

And Aunt Majida added, with a look of pride cast towards the modest Zahra, ‘This is no time for quarrelling, Mohsin Bhai. True I have done the best I could for Zahra, in the light of my own little knowledge. She has read the Quran, she knows her religious duties; she can sew and cook, and at the Muslim School she learned a little English, which is what young men want now. I did what I could, and you know in my unhappy circumstances I could do no more, even had I wished otherwise.’

At this point tears welled up in her eyes again. They flowed so easily that they had lost their significance, and were distantly related to a tale of sorrow which had lost its content through constant repetition.

It was fifteen years since Aunt Majida’s husband had left her to serve the saints to whose tombs and charities he had sacrificed the fortune which had added to his virtues when Baba Jan had chosen him as a son-in-law. It was six years since he had died, a gentle madman, possessed with his love of God. In those six years Zahra had transformed him into a saint himself; it made the chill, deserted years of her mother’s life a sacrificial offering to God.

‘Curse the Devil!’ shouted Uncle Mohsin and spat thick, red betel juice spitefully into the tall, brass spittoon standing by his chair. ‘Will you get back to the point and stop dragging me into arguments?’

‘How old did you say the boy was?’ Aunt Abida asked coldly, as if detaching herself from her anger.

‘Thirty, but he looks younger. He is handsome – well, as handsome as a man should be. Light complexioned, quite fair, in fact.’

‘Was he married into some family of your acquaintance?’

‘Yes, before he went to England for his training. He was a good husband. His wife died four years ago in childbirth. Fortunately the child died too, so our little Zahra will not be a step-mother; she will start her own family.’ He chuckled.

‘God will she flower and bear fruit!’ chanted her mother.

‘And his parents?’ continued Aunt Abida, her voice unchanged.

‘They live in the family village. Mind you, they haven’t much land, but does that matter when he is in Government service and his future is assured?’

‘Yes, his future is assured; therefore, his past need not concern us, nor the fact that his breeding is not equal to ours. What does it matter? After all he is an official—’

Uncle Mohsin rapped his stick on the edge of the takht as he raised his voice to interrupt Aunt Abida. ‘I have seen rajas and maharajas, respected friends of your father’s, laying their caps at the feet of officials. Only because they were white sahibs! The only man before whom Baba Jan bowed his head was the “Lat Sahib”, the Governor. And his daughter sits unmarried because no husband could be found equal in breeding.’

‘Mohsin Bhai,’ wailed Aunt Majida, ‘why must you talk in this manner? Why cast shadows of bitterness and anger over the future of my child? Let us wait until our brother comes, and decide with cool hearts and clear minds.’

Before she could be answered, while Baba Mian breathed the names of Allah with greater fervour, Zahra sat in demure stillness, and I achingly watched the tight white face of Aunt Abida, angry voices sounded in the corridor, and Hakiman Bua shuffled to the door, calling urgently:

‘Abida Bitia, come quickly.’

Aunt Abida started, instinctively looking towards the door leading to her father’s room. Then she turned angrily and said, ‘Stop that noise out there! Abba is sleeping.’

Baba Jan was asleep in his room, but he was everywhere as always; and the long threat of dying added to his power.

I followed Aunt Abida out of the room because it was crowded with the presence and thoughts of Uncle Mohsin. Zahra was already in the corridor; her curiosity gave her mobility. It had the same quality that had crowded into the corridor several maid-servants, the orphan boy who helped the cook and the wives of the gardeners and watchmen.

They were all staring at a smaller group in the foreground. Jumman, the washerman, stood murderously over his daughter Nandi, who cowered at his feet, shielding her head from the blow that lingered in his eyes, while his wife shaking with anguish leaned against the wall, her sari pulled over her head and hiding her face.

‘Bitia! I appeal to you!’ he called, the words forced out of his trembling lips.

‘Silence,’ Aunt Abida said angrily. ‘Have you taken leave of your senses, coming here shouting and screaming?’ She moved through them like a blade. ‘Follow me outside.’

The silent procession shuffled behind her through the rooms to the courtyard. A soft breeze rustled the leaves of the palms in their giant red pots. On the steps to the lawn the parrot sunned himself in his silvered cage and chanted as he swung, ‘Piaray Mithoo. Mithoo Betay. Allah il-Allah.’ He parodied Hakiman Bua’s voice.

‘Jumman, whatever possessed you to burst into the house and bring down the skies outside the very doors of Abba Jan’s room?’

The exaggeration of her words did not rob her voice of authority. But then all emotions seemed distended in this circumscribed household.

‘Bitia,’ said Jumman, ‘I would willingly have killed her, but this woman, her mother, said I should come to you for judge-ment. Forgive me, huzoor. My honour was besmirched, and I felt possessed by a thousand devils. I leave her now to you to do with as you will.’ And he pushed Nandi roughly forward.

Jumman in anger seemed a stranger. His dark face, with its thick moustache in contrast to his cropped head, was made gentle by large dark eyes that held no challenge. He wore a thick silver bangle on each wide wrist, and a gold ring in one ear. His loin-cloth, white and spotless, was drawn high above his bony knees, because he stood long hours in the tank wash-ing clothes, beating them against the tilted, corrugated board with a steady strong rhythm of breath and movement.

But now his eyes were squinting, and his voice was harsh. And he prodded Nandi with his foot as she huddled on the ground, hiding the face that Hakiman Bua used to say would be a scourge to her parents because it was not the face of a girl of the lower castes.

When I was younger Nandi was my favourite playmate, carelessly happy, fearless and free, graceful as a gazelle. When I was disrespectful Hakiman Bua said it was because I played with servant girls. I used to slip away to find Nandi in her steaming little room in the servants’ quarters piled with damp clothes, hot with the coals kept ready to feed heavy, black, fire-bellied irons.

Nandi’s favourite game used to be to act the bride, concealed in the thick hedge by the fountain so that no one would see this shamelessness. I used to perform the ceremony of showing the bride’s face for the first time to assembled guests, removing her hands from her face with its tight- shut eyes, tilting up her chin, saying ‘Masha Allah! The bride is beautiful’ and pressing imaginary gifts into her limp palms.

But now when Nandi’s hands covered her face it was no game she was playing. Those were not the copied conventional tears of a bride that seeped through her fingers.

‘What mischief has she been up to now?’ Aunt Abida asked sharply.

Not long ago, Nandi had thrown an accurate and sharp stone at the groom of the English family next door, because he had peeped over the wall while she bathed in the enclosure where there was a tap for the women. A few days later she had bitten the postman, saying he had attempted to molest her.

‘The wretch was found by the driver with the cleaner in the garage,’ said Jumman, hoarse with shame and anger.

‘I went to give him a shirt that he had forgotten,’ whined Nandi.

‘Be quiet, shameless hussy,’ thundered Jumman, ‘I have forbidden her to visit the men’s quarters alone, Bitia. I had to suffer the indignity of seeing her dragged home by Driver Ji, and to hear his accusations. I cannot now live in the same compound as those two.’

From Noor Khan, the driver who had been in the household only three years, my aunts observed purdah. Jumman and Jumman’s father before him had worked with the family since boyhood, and they came from our village.

Aunt Abida turned wearily to Uncle Mohsin and said, ‘You had better ask Noor Khan what happened. This is a matter for a man to deal with.’ Uncle Mohsin prodded Nandi with his silver-topped stick contemptuously. ‘This slut of a girl is a liar, a wanton.’

Nandi looked up with fear- crazed eyes, looked round at that cruelly silent, staring ring of trappers and cried out: ‘A slut? A wanton? And who are you to say it who would have made me one had I let you?’

Uncle Mohsin’s face was distorted as he raised his stick and hit her across the shoulders. She fell forward, and as I ran towards her the next blow glanced across my arm and I screamed, ‘I hate you, I hate you’, and ran blinded by tears to my room.