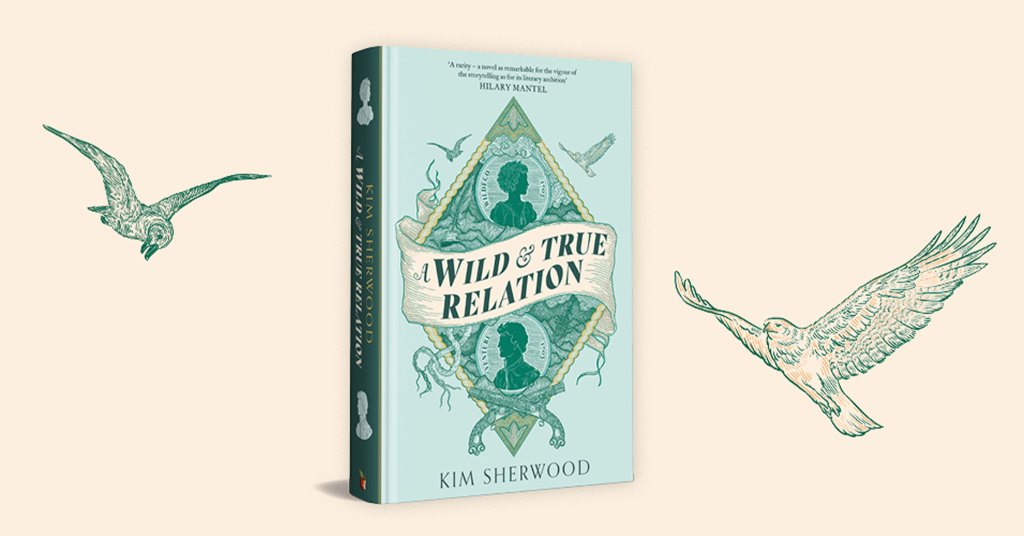

Read an extract from A Wild & True Relation by Kim Sherwood

‘Remarkable’ HILARY MANTEL

A Wild & True Relation is a gripping feminist adventure story of smuggling and myth-making, by award-winning author Kim Sherwood

The Great Storm of 26 November

If there was anything more frightening than God’s fury, it was Tom West, trying to hold his temper.

The skies rained salt water. The world turned upside down, waves lifted into clouds. High tide blanketed Bantham Beach and slammed against the cliffs. The Avon surged, breaking its banks. The tempest destroyed Grace Tucker’s garden, ripping up tender buds and frostbitten roots, until finally forcing the front door of the cottage open, admitting the violence of the night.

Grace stood in the parlour, boxed between Tom West, the boy Benedict and the struggling fire – the heart of her home, black from providing heat for food and light for the table, which was stained too, with ink spills and the scratches of a child’s first pen strokes. Now, the flames were reduced to embers, just as the kitchen seemed to shrink with Benedict hovering in the cross- passage and Tom leaning against Molly’s bedroom door. The column of Tom’s body had collapsed, those huge shoulders dragging on a failing back. In one hand, he held her journal.In the other, a pistol.

‘Please, Tom,’ said Grace. ‘Tell me what’s happened.’

Tom raised the book. In the firelight, he could make out where Grace had pressed nib to leather: A True Relation of My

Life and Deeds.

‘You must have kept this little confessional somewhere safe when I came around. Strange, to find it out tonight, with all the fineries I bought you. As if you was packing. As if you was running, while Devon drowns. And with my name on nearly every page.’

‘It has only my life,’ said Grace. ‘I write it for Molly. And – for myself. There is nothing harmful in that. Please, tell me what is wrong – why have you brought this boy here?’

In the doorway, Benedict felt every bit the boy she called him. He had never met Tom’s lover before. None of the crew had. Whenever they came ashore, ship burdened with barrels of brandy or chests of tea, Tom came here. The crew whispered about it: Tom West and his lover, a woman with a child begot by another man, Grace Tucker’s dead husband, Kit. But never in front of Tom. No one told him he was a lucky devil, having a lady of quality to lie with whenever he wished, the likes of her reduced to a cottage like this, and only him for company; no one said how strange it was, Tom caring for a bairn with nothing of his blood in its veins. Yet this was more than a warm bed and pottage in the morning. Benedict understood that now, but not why Tom had raced here, tonight, as cattle drowned and church bells clamoured, rung by the gale. What did Grace Tucker mean to the men they’d dragged from the river, smugglers and Revenue bleeding alike?

He shuffled back. ‘We should go,’ he said. ‘The horses—’ ‘No harm in it?’ Tom said, cutting through him. ‘Then I take it there is none of my movements in this masterpiece of yours?’ ‘What do you mean?’ said Grace.

‘A little late to play the fool, my love.’

‘I play at nothing.’

‘No?’ said Tom. ‘Then it weren’t your words in the ears of Dick English that got me and my men ambushed tonight?’

‘Ambushed?’ Grace edged back, the heat of the fire against her calves.

‘Captain Dick English and his Revenue was waiting by the tidal road at Aveton Gifford,’ said Tom. ‘The wind has been up all week. Only you knew I’d venture it anyway. Only you knew the profit at stake, and the satisfaction I’d get, seeing a storm in view and riding it. Only you knew where I’d bring the goods in. Nero and Daniel are dead. Shot while rowing. No warning, no chance.’

Grace paled. ‘Are you hurt?’

Tom laughed. He squeezed the pistol’s walnut grip, his fist swelling like a joint of pork strung too tight. ‘Would it matter?’

‘How can you ask such a thing?’

‘Someone told them the Yeovil crew had let me down, and the wagons would have no batmen. Someone told them I’d land at Burgh and carry up the Avon myself. Someone didn’t care

if I was lain down to die tonight.’

‘That boy you told me about – Frank Abbot. He was seen talking to the Revenue,’ said Grace, ‘before he . . . left, for Barnstaple. He must have told Captain English.’

Benedict noticed Grace picking at a loose strand from her skirt. Everyone knew what had happened to Frank Abbot, but no one spoke of that, either. The villagers praised Tom’s name

as they always had, sprinkling the salt he carried from France on their food.

Tom licked his lips. ‘What makes you think Frank left for Barnstaple?’

Grace glanced at the pistol. It was shaking in his hand. It was years since she’d asked how many of the rumours were true: if that pistol acted as just a warning, remaining in his belt, or if he was free with it. She knew how gently he could hold a child. She also knew how anger could change his face.

Now, she said, ‘I heard some fishermen talking. Frank Abbot gave the Revenue information about you and was found dead on Burgh Island. I know you ordered it, or did it yourself.’

Tom’s grip went slack on the gun and then tightened quickly before he dropped it. ‘And haven’t you got a whole load of docity, coming out with it. Or maybe that’s just what you do best.’

‘Whatever you think I have done,’ said Grace, ‘you are wrong.’

Tom fought for air. He was burning: nerve endings seared from diving into freezing water to haul his men out; thigh grazed by a bullet; bruised ribs. He was swaying on his feet. He was falling into Grace’s green eyes. Green like the land I love, that’s what he’d told her. But not blue, like the sea you love more. Her words. One foot on land, one leg in water. He had mounted a dead officer’s horse and left his crew by the tidal road, driving the animal here as fast as he could against the hail. Benedict followed – at Hellard’s command, no doubt – arriving minutes later. Tom would not tell Benedict to leave; he could keep his temper in check as long as the boy was there to witness him, with that lamblike worship.

‘I’ve been good to you,’ he said. ‘Better than your precious husband ever was, or would have been. I’ve loved your daughter, when any other man would have scorned your bed for having a child crawling into it. I’ve – you know, Grace. You know what I feel. I’ve trusted you with my life, and the life of my crew. I thought I had cause.’

‘Please, Tom, step away from Molly’s door.’

‘You think I’d hurt her?’ Tom snapped, making both Grace and Benedict jump.

‘No,’ said Grace, her hands up. ‘Please, just sit with me. Please.’

‘Captain, we’ve got to go,’ said Benedict. ‘The storm will bring this house down.’

Tom breathed through his nose. There was the pile of lace and linen he had bought Grace, folded on the table, ready for a bag.

She was going to leave him. She had betrayed him, and now she was going to leave him.

‘I’ll sit with you, if that’s what you want,’ he said, gaze locked with hers. ‘Benedict, get out. Go.’

‘But—’

‘Now.’

Benedict wormed on the spot, and then twisted away, back down the cross- passage and out the front door. The world was black, water and hills and sky merging, solid. He couldn’t find the horses. He hung on to a damson tree, unable to escape.

In the kitchen, Grace and Tom sat across from each other at the table, as they had for the past three years. Tom’s legs barely fitted. Grace perched on the edge of her chair. He set her journal down. His dark curls hung wet and filthy in his eyes. Grace reached for him, fingers skirting his swollen knuckles. Tom hunched, gripping the pistol closer.

‘There’s blood on your hands,’ she said.

‘Yours aren’t looking all that clean, either, sweetheart.’

Seconds passed. From the other room came the sound of Molly crying. Grace rose. Tom’s hand shot out, holding her where she was.

‘Molly needs me,’ she said.

‘I need you,’ said Tom. ‘I need you to tell me. Did you talk?’

Grace looked over his face and then down to his fingers tightening on her arm.

‘I can explain.’

Tom leapt up, his chair falling. Grace jerked away, but he held on. They were bound up with each other, flailing and catching. One of them knocked the cutlery and pewter plates, and the last of Grace’s ink shattered. Tom shoved Grace into the bookshelf. He grabbed a fistful of her hair, smashing her face into the wood.

‘How could you do this? How could you?’

Grace cried for him to stop. Tom threw her away from him. She fell to the floor, landing in a nest of broken leather spines and torn fleshy parchment. Her lips were split and her chin glistened with blood. Tom stood above her. He watched Grace turn her head towards Molly’s door. Then she was still.

Tom dropped to the floor. ‘Grace?’ He pawed her chest, burying his face into her hair. ‘Grace? Why did you do it?’

His snot felt warm on her scalp. Grace tried to speak, forcing her lips to shape the words she needed. ‘I never intended . . .’

‘Tell me it was a mistake, you wrote it down and someone read your journal without your leave.’ Tom stroked her cheek, her neck. His fingers dug into the hollows of her tendons. ‘Tell me it was a mistake. Grace, tell me, now. Please . . . ’

‘I had to do it—’ He was squeezing too hard.

Benedict stood in the threshold of the cross- passage watching. His feet would not take him any further than he’d already travelled, nor retreat to the storm outside. Bile clogged his

throat. Tom was going to kill her. Benedict gripped his knife. She was to blame. Benedict had watched his friends die and she was the reason. Sweat melted the ice clinging to his clothes.

Tom was going to kill her.

He had to do something. In the name of God, he had to do something. A cry outside. It could be a villager, come to check on Grace in the storm, or a Revenue man – or one of Tom’s

crew, come to help.

Benedict ran outside. A shaky orb of light slipped down the hillside. A cry. Hellard.

‘I’m here!’ Benedict shouted. ‘Help!’

‘Benedict?’ Hellard’s voice was whipped by the wind.

Lightning slapped the garden white. Hellard fell next to

Benedict, seizing his arm. ‘Where’s Tom?’

‘Inside, with that woman.’

‘Why?’

‘She told the Revenue. Tom’s lost his mind—’

Hellard pulled his pistol free.

‘Hellard, what are you doing?’

Hellard shoved past Benedict, the lantern’s glow retreating inside. Benedict remembered the blood beneath Hellard’s fingernails after his talk with Frank Abbot. He hurried

after him.

At the kitchen door, Hellard clambered over the building dam of branches and silt washed in from the Avon. The dancing beam of the lantern spilt into the parlour. Tom sat slumped

on the floor, holding his head. Grace lay next to him. She was peering up at the wooden beams, breathing heavily. Her neck was red. A door opposite rattled: small hands on the other side

beating the wood.

‘Did she talk?’ said Hellard.

Grace shifted on the floor. Glass grated her scalp. She lifted herself on one elbow, looking from Hellard to Molly’s door.

‘What have you come here for?’ said Tom. ‘Get out.’

Hellard, louder: ‘Is it true?’

Tom picked his pistol up, shaking off the dust. He rose until he had to duck his head to avoid hitting the beams, and looked down at Hellard. ‘Be on your way, brother.’

‘Tom, you can’t let her off. If it was anybody else, you’d kill ’em. That’s law. If you don’t be able, I swear to the devil I will.

Nero and Daniel, they’re both dead. Oliver was bleeding out when I made my way here. I’ll do it, if you won’t.’

‘Not while I’m standing,’ said Tom.

Hellard lunged for Grace, but Tom barred the way.

‘You gutless bastard!’ Hellard wriggled in Tom’s fist, pistol waving, the butt striking Tom’s chin. Tom tossed Hellard back. ‘Do it!’ screamed Hellard, raising his pistol, not quite at Tom,

but inching closer. ‘Or get out of my way.’

A bang shook the walls. Benedict’s heart lurched. Ears clouded. He couldn’t hear anything. But there was no smoke. There was no gunshot.

Someone was kicking at the door.

Benedict stumbled down the passage, praying for Nathan or Kingston, anyone whose word of calm or humour might douse

the fury of the Wests. The front door swung back.

‘Aside, boy! Where is she?’

Benedict’s flesh pricked. He knew that bark: Captain Dick English, who tonight had cut them down. Benedict raised the knife. The Book of Common Prayer came to him then, the succour of childhood, sealing him in time: From lightning and tempest; from plague, pestilence, and famine; from battle and murder, and from sudden death, Good Lord, deliver us. He tackled the oncoming

body, but Dick was a bull to his billy goat and Benedict was cast aside, head bouncing against the wall.

Inside, Grace seized the mantel and heaved. She leant against the wall. Hail clattered down the chimney like dice from trembling hands. A handful of sparks spattered on the rug. The room was dim and the voices muffled. She knew she was still in the kitchen, yet was certain she could smell spring garlic, whole shafts crushed underfoot in the wood where she walked with Molly, showing her daughter the flowers, lifting her on to the fallen oak. The tree had been struck by lightning and the roots were sooty. If Grace stroked them, her fingertips came away black and she could write Molly’s name on the pale strips of bark. Tom had written his name, too, next to Molly’s and Grace’s, the first time he came with them. His name was the only word he knew how to spell, once.

‘Tom,’ she said. ‘I have never seen you a coward. Don’t be a coward now.’

Tom slowly turned his back on Hellard’s gun, and faced her.

He stared into her eyes. Green like the land I love. He could hear Molly screaming. He had lifted her, mottled red and brown and crying to know the world, into Grace’s arms in her first minute.

The pistol in his hand twitched. Turn and shoot Hellard – break every oath he’d sworn to their mother. The gun twitched higher. He could shoot Benedict too, that sweet young boy, if it came to that. A little higher. He could leave this life, its power, its wealth, and take Grace and Molly away. He could lie beside Grace’s betrayal every night. Give it all up for a woman who would see him die alone in a ditch. His arm was fully stretched now, the pistol accusing her.

‘Be a man,’ she said.

Tom raised a hand to cover his eyes, but faltered midway. He took all of her in.

Grace looked at him with love.

He clicked the hammer back. Fired.

Hellard flinched, stepping back and knocking into Dick English, who barrelled into the room with his pistol and sword

drawn. Hellard swung with his gun, catching Dick in the temple. The lawman dropped to the floor. Hellard laughed, using the tip of his boot to tilt Dick’s head this way and then that. Out cold, a scarlet ribbon threading through his golden locks. Pathetic.

Benedict stood in the doorway to the parlour, his eyes shut. The last thing he’d seen was Dick English cocking his pistol and kicking his way through the ruins into the room. Then a flash, and Grace’s short cry and the thud of muscle and bone hitting the floor.

The child’s wails were deafening. Benedict hugged his ears. It would not stop. It would not—

‘Benedict.’ Hellard was shaking him. The man righted a chair and pushed him into it.

Benedict looked around. ‘Where’s Tom?’ ‘In there,’ said Hellard, nodding at the closed door.

Benedict could hear little soothing sounds coming from the child’s room, broken up by sobs. Deep, male sobs. He said, ‘I’ve never seen a woman killed before.’

‘Don’t be looking, then. Fifteen years to your name and wet as a babe.’

Benedict was aware of Grace’s outstretched hand, her fingers curled like the opening head of a crocus. Her gown had come open, revealing faded freckles and pale breasts. A canker worm twisted deep in him. Next to her, Dick English lay in the wreckage. His pistol remained in his hand, just as Hellard’s did. ‘What are you doing?’ said Benedict.

‘Helping the storm along,’ said Hellard. ‘What she want with a beaufet fine as this in a damn hovel, anyway?’ He knocked the glass- fronted cupboard over. To Benedict, the boom of smashed crockery was as loud as the ship’s bow slamming on to a wave. ‘First time anyone’s been happy to see Dick English, I’ll warrant – even his mother, on the day she spat him out.’

‘She thought he’d save her?’ said Benedict.

Hellard laughed. ‘If she did, she was disappointed. He shot her.’

Benedict breathed: ‘Why . . . ?’

‘Aiming at Tom. Whore got in the way. Ain’t it tragic? Still, saved me and Tom some unpleasantness.’ Hellard kicked the bookshelf. ‘Here, look at this.’ He picked up Grace’s journal.

Benedict glanced at Grace. ‘It’s hers,’ he said. ‘A True . . . something.’ Benedict looked again at the pistol in Hellard’s fist.

‘It was Dick, then, who shot her?’

‘As much as I’d like to take the credit . . . ’ Hellard crossed to the fireplace. He stooped to the dying flames.

Tom stepped over Grace’s body without looking down. He held Molly in his arms, pressing her face gently into his shoulder. She was six years old and fitted perfectly into his torso. She had lain along Grace’s forearm when she was born, her head cradled in the crook of her mother’s arm, her wet buttocks and squirming legs held steady in Grace’s sure hand.

The child’s blonde ringlets were touched by rust, Benedict saw – Grace’s blood – and her toes recoiled from the pistol in

Tom’s belt.

Tom said, ‘Don’t.’

Hellard: ‘Tom, if someone found this—’

‘Don’t.’

Hellard held the book by its tired spine, pages swinging loose. The last page to be written had already turned brown.

He sighed, offering it up. Hugging Molly closer, Tom slipped the journal into his coat.

‘What are you going to do with the boy?’ said Hellard. ‘Now Dick English has killed his mother?’

Tom paused, reading Hellard’s face: the weighted glance at Benedict, the question posed. Why not be the hero, and cast Dick as villain? It’ll be our little secret.

Benedict was looking at the child. Molly, Grace had called her. But she did wear breeches and a woollen waistcoat – cut down, Benedict realised, from one of Tom’s. He waited for Tom to correct Hellard, but, after a slow silence, he just said:

‘Boy’s mine.’

‘Stray shot of yours?’ said Hellard. ‘I always thought you were niggling her, ’neath Kit’s nose.’

‘I don’t know about your shots, Hellard, but I hit what I aim at.’

Hellard blazed redder than the fire. A scene opened before Benedict: it was Hellard whose shot had gone wide; wretched power- starved Hellard who had fired at Tom, and Grace stood in the way. No, it couldn’t be – for Tom wouldn’t allow the curtain to fall on a scene such as that with no answer. Hellard’s cheeks must be reddening because Hellard himself was a stray shot: Tom’s bastard half- brother, a cuckoo who lived under big brother’s wing.

Tom wasn’t paying any mind. He was looking down at Grace, seeming to Benedict like a man trying to solve some point that would always defy him. He spoke distantly: ‘Grace would have none of me, while that bond still existed. But the boy’s mine now.’

‘What do you want with an orphan?’ said Hellard.

Tom looked to Benedict, whose face was blotted with tears; he stood under the weight of the boy’s stare a long moment, his fingers twitching. Then Molly whimpered and Tom looked down, kissing her head, tasting copper. ‘Let the house burn,’ he said, and turned his back on both of them, stopping just for a moment to consider English, who lay motionless in his own blood. ‘And let the devil burn with it.’

As Tom walked out, Benedict could hear him whispering, deep and gentle: ‘I’m here, child, I’m here. You’re safe.’

Discover the book: