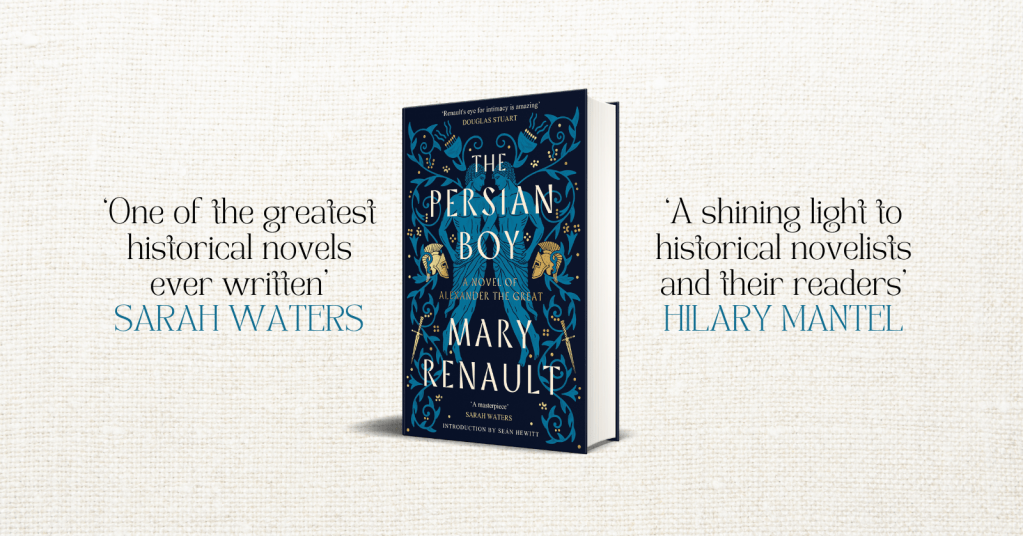

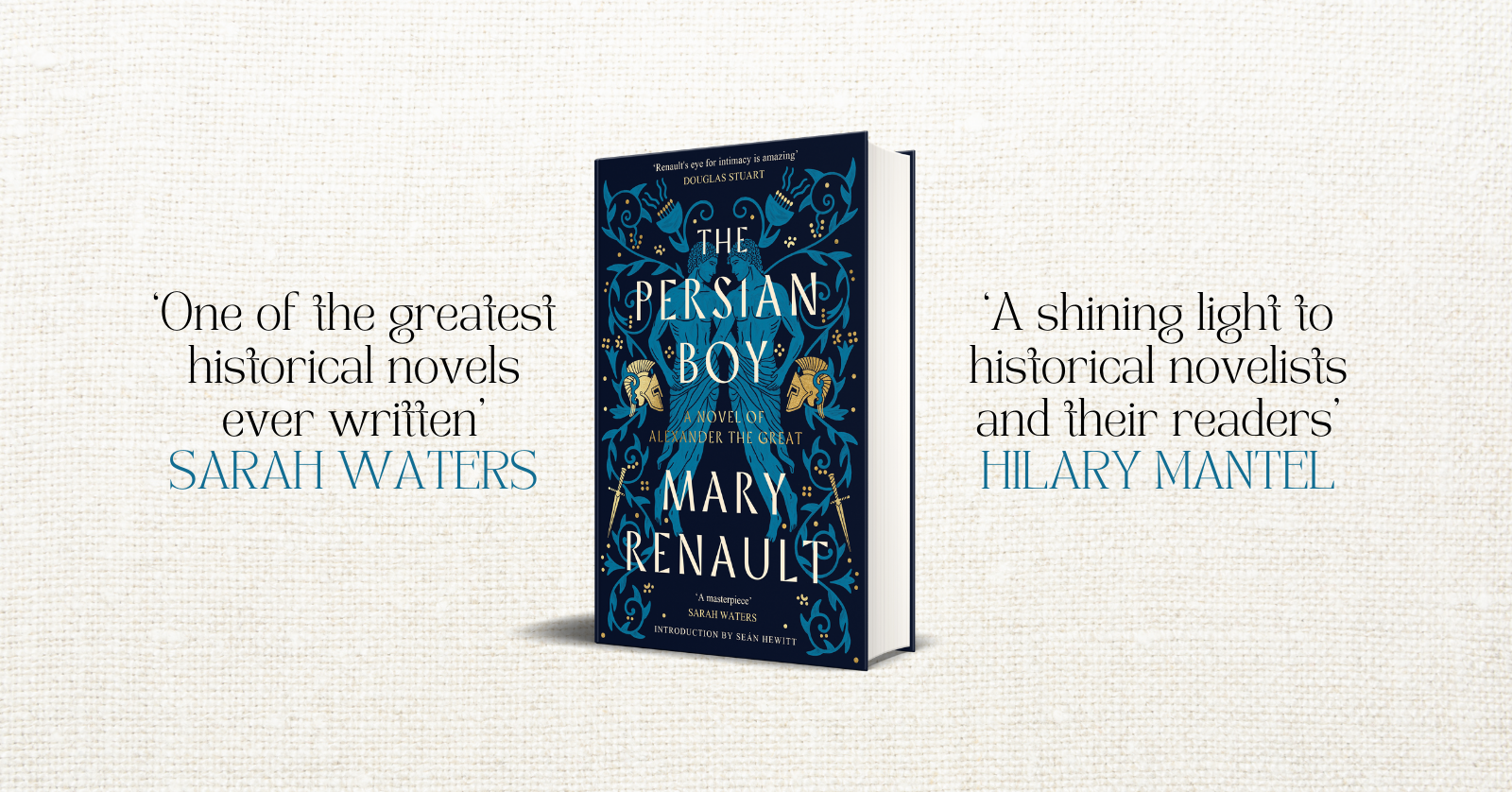

Read an extract from The Persian Boy by Mary Renault

‘One of the greatest historical novels ever written’ SARAH WATERS

‘I love to find queer representation in historical fiction. . . Renault’s eye for intimacy is amazing’ DOUGLAS STUART

‘The Alexander Trilogy stands as one of the most important works of fiction in the 20th century . . . Renault’s skill is in immersing us in their world, drawing us into its strangeness, its violence and beauty’ THE TIMES

A groundbreaking queer classic and vivid reimagining of the last years of Alexander the Great, told through the eyes of his lover.

Read on for an extract from Chapter 2:

Two years I served the harem, suffering nothing much worse than a tedium I wondered, sometimes, I did not die of. I grew taller, and twice had to have new clothes. Yet my growth had slowed. They had said at home I would be as tall as my father; but the gelding must have given some shock that changed me. I am a little better than small, and all my life have kept the shape of a boy.

None the less, I used to hear in the bazaar praise of my beauty. Sometimes a man would speak to me, but I turned away; he would not speak, thought, if he knew I was a slave. Such was still my simplicity. I was only glad to escape the women’s chatter, see the life of the bazaar, and take the air.

Presently my master also gave me errands, taking notes to the jewellers of his new stock, and so on. I used to dread being sent to the royal workshops, though Datis seemed to think he was giving me a treat. The workmen were all slaves, chiefly Greeks, who were prized for skill. Of course they were all branded in the face; but as punishment, or to stop their getting away, most of them had had a foot off, or sometimes both. Some needed both hands and feet, if they used a burin-wheel for carvinggems; and these, lest they should slip off untraced, had had their noses taken. I would look anywhere but at them; till I saw the jeweller watching me, supposing me in search of something to steal.

I had been taught at home that, after cowardice and the Lie, the worst disgrace for a gentleman was to trade. Selling was not to be thought of; one lost face even by buying, one should live off one’s own land. Even my mother’s mirror, which had a winged boy engraved on it and had come all the way from Ionia, had been in her dowry. No matter how often I fetched merchandise, I never ceased to feel the shame. It is a true saying, that men don’t know till too late when they have been well off.

It was a bad year for the jewellers. The King had gone to war, leaving the Upper City dead as a tomb. The young King of Macedon had crossed to Asia, and was taking all the Greek cities there from Persian rule. He was not much more than twenty; it had seemed just a matter for the coastal satraps. But he had beaten their forces and crossed the Granikos, and was now thought as bad to reckon with as his father.

It was said he had no wife; that he took no Household with him; only his men, like a mere robber or bandit. But thus he got about very fast, even through mountain land unknown to him. From pride he wore glittering arms, to be singled out in battle. Many tales were told of him, which I leave out, since those that were true are known by all the world, while of the false we have enough. At all events, he had already done all his father had intended, and still did not seem content.

The King, therefore, had mustered a royal army, and gone himself to meet him. Since the King of Kings did not travel naked to war like a young western raider, he had taken the Court and Household, with its stewards and chamberlains and eunuchs; also the harem, with the Queen Mother, the Queen, the Princesses and the little Prince, and their own attendants, their eunuchs and hairdressers and women of the wardrobe and all the rest. The Queen, who was said to be of surpassing beauty, had always brought the jewellers good trade.

The King’s attendant lords had also taken their women, their wives and often their concubines, lest the war should last some time. So, in Susa, only such people were buying jewellery as are content with chippings stuck in paste.

The mistress had no new dress that spring, and was sharp with us all for days; the prettiest of the concubines had a new veil, which for a week made life unbearable. The Chief Eunuch had less shopping-money; the mistress was skimped with sweets,the slaves with food. My only comfort was to feel my slim waist, and look at the Chief Eunuch.

If no thicker, I was growing taller. Though I had again outgrown my clothes, I expected to go on wearing them. But to my surprise, I got a new suit from the master; tunic, trousers and sash, and an outer coat with wide sleeves. The sash even had gold thread in it. They were so pretty that I stooped over the pool to see myself, and was not displeased.

The same day, soon after noon, the master summoned me to his business room. I remember finding it strange that he did not look at me. He wrote a few words and sealed the paper, saying, ‘Take this to Obares the master jeweller. Go straight there,don’t loiter in the bazaar.’ He looked at his fingernails, then back at me. ‘He is my best customer; so take good care to be civil.’

These words surprised me. ‘Sir,’ I said, ‘I have never been uncivil to a customer. Does anyone say I have?’

‘Oh, tut, no,’ he said, fidgeting with a tray of loose turquoises. ‘I am only telling you to be civil to Obares.’

Even then, I walked to the house thinking no more than that he had some worry about the man’s goodwill. The captain who took me from my home, and what he did to me, was smothered up with other things in my mind; when I woke crying in the night, it was mostly from a dream of my father’s noseless face, shouting aloud. Without thought of harm I went to the shop of Obares, a stocky Babylonian with a black bush of beard. He glanced at the note, and led me straight through to the inner room, as if I were expecting it.

I hardly remember the rest, except his stink, which I can recall today; and that, after, he gave me a bit of silver for myself. I gave it to a leper in the marke-place, who took it on a palm without thumb or fingers, and wished me the blessing of long life. I thought of the monkey with green fur, carried away by a man with a cruel face, who’d said he was going to train it. It came to me that perhaps I had been sent on approval to a buyer. I went to the gutter and vomited my heart out. No one took notice.

Damp with cold sweat, I returned to my master’s house.

Whether or not Obares would have been a buyer, my master was not a seller. It suited him far better to be doing Obares favours. I was lent to him twice a week.

I doubt my master ever called himself what he was. He just obliged a good customer. Then a friend of Obares heard, and must be obliged for his sake. Not being in the trade, he paid in coin; and he passed the good word on. Before long, I was sent out most afternoons.

At twelve years old, it takes too perfect a despair to die alone. I thought of it often; I had dreamed of my father without his nose, and instead of the traitor’s name he shouted mine. But Susa has not walls high enough to leap from; there was nothing else with which I could make sure. As for running away, I had for example the leg-stumps of the royal jeweller’s slaves.

I went, therefore, to my clients as I was told. Some were better than Obares, some much worse. I can yet feel the cold sinking of my heart, as I walked to some house unknown before; and how, when one required of me something not fit to be described, I remembered my father, no longer a noseless mask, but standing on the night of his birthday feast while by torchlight our warriors did the sword-dance. To honour his spirit, I struck the man and called him what he deserved.

My master did not beat me with the leaded whip he used upon the Nubian porter, for fear of spoiling me; but the cane cut hard. While it still stung, I was sent back to beg pardon and make amends.

This life I led for rather more than a year, seeing no escape till I should be too old. My mistress did not know of it, and I conspired to deceive her; I had always some tale for her of my day’s business. She had more decency than her husband, and would have been outraged, but she had no power to save me. If she knew the truth, the house would be in an uproar, till for the sake of peace he would sell me for the best price I’d fetch. When I thought of the bidders, I kept the hand of discretion before my mouth.

Whenever I passed through the bazaar, I imagined people saying, ‘There goes Datis’ whore.’ Yet I had to bring back some news, to satisfy my mistress. The rumours were running, ahead of truth, that the King had fought a great battle with Alexander, at Issos by the sea, and lost, escaping with his bare life on horseback, leaving his chariot and his arms. Well, he got away, I thought; there are some of us would think that luck enough.

As proper news came in by the royal road, we learned that the harem had been taken, with the Queen Mother, the Queen, her daughters and her son. I pitied them; I had good cause to know their fate. The girls’ screams rang in my ears; I pictured the young boy flung upon the spears, as I would have been but for one man’s greed. However, never having seen these ladies, and being bound for the house of someone I knew too well, I kept some pity for myself.