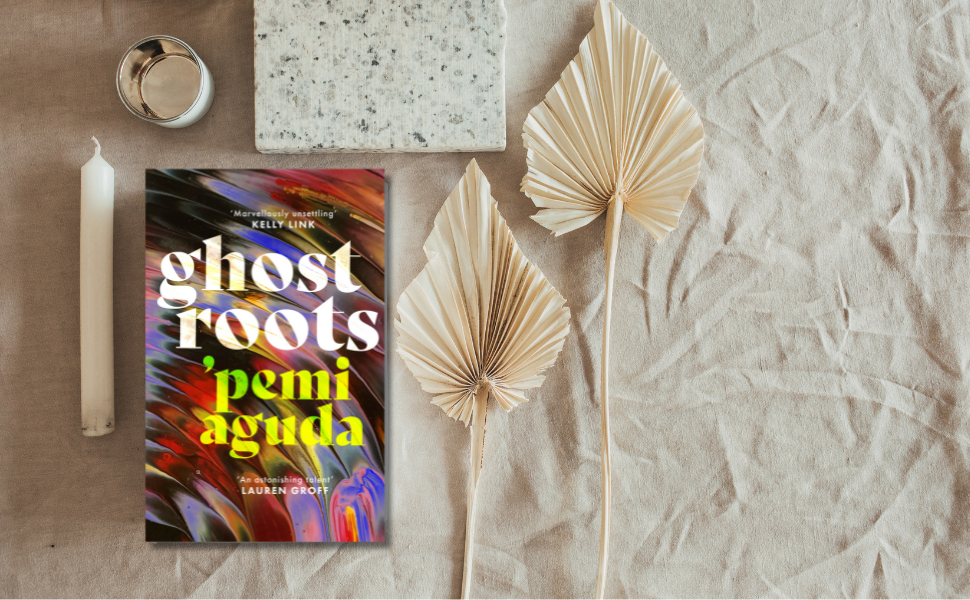

Read an extract from Ghostroots by ‘Pemi Aguda

The supernatural looms over the grime and sweat of everyday life in Lagos in this dazzling collection of stories from a prize-winning young Nigerian writer.

MANIFEST

◊ ◊ ◊

THIS IS THE FIRST PIMPLE OF YOUR LIFE. Question the foreign object with all your fingers.

If you were to draw a straight line down from the right corner of your lip, then another straight line forward from the corner of your jaw, the pimple would be sitting at that intersection. Your index fingernail—false, acrylic, painted a burnt orange—flicks at the tiny bump. You press the pad of your thumb down on it, hard. The pimple does not go away. You have just turned twenty-six, why now?

Tonight, your mother calls you Agnes for the first time. Agnes is not your name.

You are sitting at the dining table, picking beans, picking at this pimple. You like to sort beans on the wide surface of the mahogany table that’s older than you, sliding weevils and broken beans to a corner, making a route through the good beans so that you never have to lift them up. You think of the bad beans and weevils as lepers, driven out of the colony to live amongst them- selves in disease and brokenness forever. When a weevil starts to creep back to the good beans, you stab at it. You love to feel them die. The crunch, then the give, under the force of your finger. Flick the dead off, stab again. Your mother must have been standing there awhile because when you look up, there she is, frozen, gripping her Bible and hymn book bag to the gold buttons of her nineties suit. The illumination from the hallway bulb envelops her so that her edges are blurred. Half of her face eaten by light.

“Agnes?”

“Hmmn?” you ask. “Who’s that?” But your mother only shakes her head, retreating.

“Who is Agnes?” you ask your father later that night. He is eating while watching a news report on the South Sudan civil war. Since the start of the conflict, almost two million people have been internally displaced . . .

You sit at the foot of his armchair, pulling hairs from your arm in the glow of the television screen. Agnes is your mother’s mother, your father tells you. “She died when your mum was young, ṣ’oo mọ ni?” He questions your ignorance as he makes vile noises with his tongue and teeth in an attempt to dislodge beef. But what do Nigerian parents tell their children about their own parents? Especially the Pentecostal Christians? Nothing. If you took a poll of your friends, three out of five would be similarly ignorant of these histories of parents who moved from somewhere to Lagos, left behind reli- gions and curses and distant cousins and grimy pasts.

You ask your father if he wants more beans and beef, your hand back on that pimple. He shakes his head no. Your father hates that you take the weevils out of the beans; he thinks they add a certain flavor to the dish.

◊ ◊ ◊

THE SECOND TIME your mother calls you Agnes, your little family of three is sitting in relative darkness. Electricity is out again and fuel scarcity means that you only see each other in candlelight until the power is restored. Your father snores in the gray-turned-brown armchair you call “Daddy’s chair,” while you and your mother sit across from each other at the dining table. You pull the empty Milo tin that the candle is mounted on closer to yourself. Wax sloshes off slowly and trickles down a side. You close your left eye, then the right, then the left again, enjoying the way the flame shifts. You draw the candle even closer, sniffing at the flame.

Your mother’s face lifts from her phone screen and watches you. Through your left eye, you see her eyes widen. Through your right eye, you see her mouth open. Through both eyes, you see terror spread over her face, the way it does when a flying cock- roach is in the vicinity.

“Agnes?” Your mother’s voice is all croak and phlegm. “Agnes, is that you?”

You lift the candle to your chin to illuminate, pulling it slightly back when heat licks at that stubborn, still-there, solitary pimple. “It’s me.” Pause. “Are you okay?”

Your mother says nothing, swallows.

“Mummy, do I look like your mum? Do you look like her?”

She pushes her chair back, not answering, leaving the table in an arthropodous scurry, locking herself in the guest bathroom until the lights come back on.

“But what’s wrong with her?” you ask your father the next morning, whispering over his black coffee and your milky tea.

He shrugs. “Her mother died around your age . . . Maybe the resemblance has heightened?” He ruffles his mustache, forehead crinkled. “Be patient with your mum, the memories are hard on her.”

◊ ◊ ◊

DAYS LATER , you sit on the four layers of tissue paper you’ve spread on the toilet seat of one of Lekki’s posh restaurants as protection from the innermost liquids of strangers, and stroke at the hardness of the pimple.

You skim the inside headlines of the newspaper you picked from the top of the magazine rack. Woman Cuts Lover’s Penis Off in Rage of Jealousy. Man Beats Daughter to Death for Skipping School. Com- munity in Outskirts of Lagos Hack Thief to Pieces. You close the paper. Someone knocks, jiggles the handle, but when you don’t respond, footsteps fade away. It is then you wipe with too much tissue, stand. After you flush, your gaze stays fixed inside the toi- let bowl even when the shuddering of the machinery has stopped, after the Lekki water is as clear as it will be. You watch until the

water in the bowl stills.

The replacement tissue rolls are sitting on an open shelf under the sink. Pick them up, one after the other, throw them into the toilet bowl. All five of them. When the last one has landed on top of the others, white on white on white, squeeze up the newspaper and throw it in too. Flush again. Watch the water rise to seat level. When it starts to seep out of the bowl, through the newspaper’s print, and out to the black-and-white hexagonal tiles of the restaurant bathroom, flush one more time. Then walk out of the flooding bathroom.

◊ ◊ ◊

THE NEXT MORNING, you wake up to find the pimple gone. Lying on your back on your friend’s sofa, you spread fingers across your face, searching to see if it has moved to a new location. Your unmoisturized fingers are dry and harsh against your soft skin, so you trail every inch lightly, careful not to scratch yourself.

“If you haven’t ever had a pimple, can we say you’ve not gone through puberty?” your friends used to tease you, cupping your cheeks in their hands, plastering kisses on the smooth, taut skin of your face because you have always been the loved baby of the group, the youngest. Sweet baby-faced you.

Only when you are satisfied the bump is no longer there do you creep into the bathroom to stare at your reflection in the tiny mirror above the sink. If you lean back, away from the mirror, you can see all of your face, but no, don’t lean back. Move your face up, down, left, right, and see the parts in detail. The thin brows, trimmed too slim by the zealous makeup artist at a friend’s wedding. A wide nose, yellow sebaceous dots accenting the point where nose blends into the rest of the face. Lips that are full, too full, so that you highlight with a brown lip liner before filling in with lipstick, an attempt to thin them.

◊ ◊ ◊

THE THIRD TIME your mother called you Agnes, she hit you in the face with a Bible. Your friend Lesley is hosting you until your mother stops seeing her mother in your face, stops labeling you the reincarnation of someone who terrified her. You and Lesley both work on Awolowo Road, so you drive together every morning in the red Honda handed down from your mother. Lesley doesn’t have a car.

You move away from the mirror to get ready for work. But after you have pulled on the branded neon green T-shirt for your job at Globacom, where you spend all your hours asking how you can help customers, the pimple is back. You touch it, softly. It is tiny, almost imperceptible to the eye, but there is a hard bump underneath. You sit on the arm of the sofa that is temporarily your bed, worrying the pimple. Pinch it, press against it.

“Genes,” is what you told your friends when they teased. “I got Mama’s good skin.”

Lesley hasn’t stirred from her room this morning. She is a deep sleeper. You stare at your friend’s bedroom door, brushing at the pimple. Then you pick up your tote bag. Don’t knock on Lesley’s door, don’t wake her up even though you’re her ride to work. Jog down the stairs to your car, slam the door. Drive alone to Awolowo Road with your bag sitting in the passenger seat like a queen.

When Lesley starts to call over and over again, an hour later, sending angry WTF?!! texts, turn your phone facedown on the desk. Walk to the bathroom down the hall, lean into the mirror, and see that the pimple is gone again. Your skin is back to baby- smooth and blemish-free.

◊ ◊ ◊

YOU ASK YOUR COWORKERS if they believe in reincarnation. Five of them believe. Two of them claim to have corroborative stories.

One: A man dies from injuries sustained in the Biafra war. His widowed wife gives birth to their son months later. The little boy has dark eyes and an ear split in two, the two parts curl- ing over each other like abandoned twins. The woman traces her son’s ear, seeing her husband’s blood dripping over her fingers as she cleaned his war wounds.

Two: A man named Collins really wants an education, but he is too old and thick from years on the farm. Collins’s farming is successful, though, so when he is bitten by a snake and dies slowly in the arms of his little brother, Eze, he bequeaths his wealth to him, saying he will be back in another life to get an education. Years pass, and when Eze finally has a son after many daughters, people remark that the son loves to lick the palm oil before eating the yam, just like Collins used to. When the son falls ill at the age of ten, Eze consults the dibia, who throws cowries to consult the gods. The gods tell the dibia to tell Eze not to forget that Collins said he would be back for an education. After the boy is enrolled at a school, the strange illness disappears.

“Wow,” you say. “Wow.” But at lunch, one of the storytellers confesses to you, leaning over your plate of rice and stew, pulling at your sleeve, that he read it all on Nairaland and therefore can- not verify its authenticity.

“Nobody has a story about a reincarnated woman?” you want to know.

“Well, I know I’m Beyoncé,” your boss’s secretary says, sidling up to you in a haze of flowery perfume.

You frown. “I don’t think that’s how it works,” you tell the woman, who is stroking her blond wig as if it were a living thing, a pet that needs comfort.

“Kilode? I’m telling you I’m Beyoncé. I am Beyoncé.” She leans closer to you, her hair falling heavy to brush against your cheek; she caresses your chin, turns it so that she is looking through full false lashes into your brown eyes. She smiles a benevolent smile. “I am Beyoncé.”

◊ ◊ ◊

THAT DAY YOU LEFT HOME for Lesley’s, your mother returned from choir practice singing a hymn about Jesus and lambs and blood. You were in the kitchen cooking dinner, because you liked to cook, and you liked to cook for your parents, and you liked living with your parents, although you could afford to move, and you liked the cold of the tiles seeping into your feet and the cold of the frozen turkey hurting your fingers.

Your mother’s singing stopped when she heard you humming over the sink. She stood at the door to the kitchen, looking at you, her daughter, wearing that black-and-gold kaftan you share. Her Bible trembled in her arms when she spoke.

“Where did you hear that song?”

You turned to squint at her. “What song?” “What you were humming just now. Where?”

But you couldn’t remember what abstract tune it was—from TV? radio?—and you said as much but your mother was already bearing down on you, her terror stark.

“Agnes, why have you come back?”

You stared into your mother’s angry eyes, brown and cat- shaped, like yours, with the scanty but long lashes, like yours.

“I’m not Agnes, Mummy. I’m your daughter?” Your voice was small, frightened for the first time since the Agnes episodes began. Her face contorted; her tone, a screech. You leaned away. “Agnes, why are you back? Have you not done enough evil?”

Then your mother lifted her Bible and swung it through the air until it hit your face. The leather of the Bible stung your chin. “Agnes, I bind you! Agnes, flee, in Jesus’s name! Flee!” Your father’s voice was somewhere in the background, asking your mother if she’d gone mad. She hit you again and again, turning an eye blood-red, until your father placed his body between you and the Bible. But you did not feel pain, did you? You didn’t even flinch. What you felt was a release within you, a stirring, like a cough freeing you from a congestion in your chest.

◊ ◊ ◊

Continues in ‘Manifest’, Ghostroots by ‘Pemi Aguda.