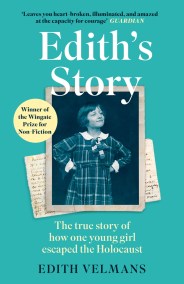

Mother’s Milk by Hester Velmans, daughter of Edith Velmans

MOTHER’S MILK

14 May 1945, Breda, the Netherlands

‘What a wonderful thing it is, a mother . . . Why do you only realize that when she’s gone?’

Those words are from my mother’s diary, written when she realized her own mother was probably not coming back from the camps in Poland.

My mother, Edith, who died two years ago, would have turned 100 this July. She spent her teenage years in Nazi-occupied Holland, hidden by a brave Gentile family who risked their lives taking her in. She lived under an assumed name with false identity papers, within sight of the German garrison across the street. There was even a Nazi officer billeted in the house; to avert suspicion she was the one to brazenly bring him his coffee in bed on Sunday mornings. At the end of those terrible years she emerged from hiding only to find out that her mother and grandmother had been deported to a concentration camp and gassed, her father died of cancer, and her brother was caught trying to escape to England and perished in Auschwitz.

Five years after the war, she gave birth to twins — my sister and me. In the Amsterdam maternity ward she befriended the woman in the bed next to hers, who, it turned out, had her own dramatic story of the war years. The other mother’s name was Miep Gies. The two of them bonded over their determination to leave the horrors of war behind and make a fresh start for themselves and their families. The subject of the war seldom came up. But when Miep saw my mother scribbling away in her diary, she did say wistfully that her boss’s daughter, Anne, had had the same hobby. Miep had saved the diary, and Mr. Frank was going to have it published.

‘Really!’ I say politely. ‘I’d like to read it someday.’

I don’t say this to Miep, but I don’t think that very many people will be interested in reading this poor girl’s diary. Lots of people must have kept diaries during the war—I know this because even I kept a diary. Anne Frank’s story must be much sadder than mine, of course, because she died. Yet even she was just one of the thousands—no, millions of victims.[1]

As it turned out, my mother’s new friend had a problem: her milk wasn’t coming in abundantly enough to sate her little boy, and he wouldn’t stop crying. Edith’s mammary glands, on the other hand, were so overstimulated that she was producing too much, even for two babies. So the nurses came up with a most practical solution: the excess milk was collected in little glass jars and fed to Miep’s baby in a bottle. After the new parents went home, Miep’s husband Jan continued to come to our house for a few more weeks to collect the milk.

That story — the post-war exchange of mother’s milk — only started to mean something to me when I had my own baby. I sat there looking down at that busy little baby skull at my breast, and started to cry, thinking of Edith’s milk for Miep’s son, how perfectly life sometimes works itself out, how miraculously all things can come full circle in the end.

As for Anne’s diary, my mother did not get around to reading it until many years later, when Anne had become a legend in the world.

Hester Velmans is a literary translator and the author of the novels Isabel of the Whales, Jessaloup’s Song and Slipper. She helped her mother turn her war diaries into an award-winning memoir, Edith’s Story (Virago Modern Classics 2025)

[1] From Edith’s Story, Virago Press 2025

_______

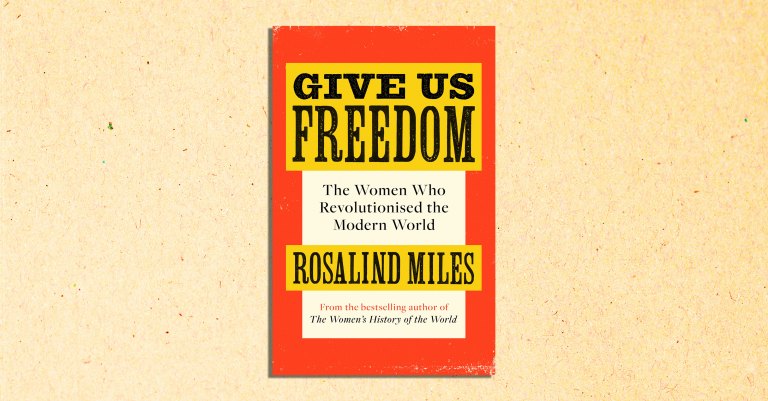

The extraordinary true story of how one young girl esaped the Holocaust.

‘I never realised that there could be such suffering in the world, and that anyone could live through it’ – from Edith’s diary, 1st July 1945

After Germany occupied the Netherlands in 1940, fourteen-year-old Edith was still filling her diary with carefree stories of school, parties and boys. But her entries soon record a darkening world. By 1942, as the Nazis escalated their persecution of the Jewish population, Edith began a bitter struggle to survive.

Hidden in plain sight but a courageous Christian family, with a German officer billeted in the next room, Edith faced the horrors of war under constant threat of discovery and betrayal. Weaving together Edith’s diaries with letters smuggled between family members and her own memories, this extraordinary memoir of ‘the Anne Frank who lived’ is a profoundly moving account of grief, loss, courage – and one girl’s remarkable belief in humanity in the face of despair.

With a new introduction by Esther Freud.

‘It holds you with the same intensity as The Diary of Anne Frank and leaves you heart-broken, illuminated, and amazed at the capacity for courage’

GUARDIAN

‘One of the best and most moving memoirs I have ever read’

RUTH RENDELL

‘It’s impossible to get through this inspiring and great-hearted volume dry-eyed’

WASHINGTON POST

‘Both memoir and meditation, it is moving and wise . . . neither sanguine nor sentimental about the Holocaust and man’s capacity for evil’

LINDA HOLT, INDEPENDENT

‘Truly moving . . . leaving one with great hope in humanity’

THE TIMES